The Untold Truth Of The Nightmare Before Christmas

When Tim Burton's The Nightmare Before Christmas premiered in October 1993, it did so with surprisingly little fanfare for a film developed by Disney. While it was lauded by the top critics of the day, it wasn't the immediate success that Burton, director Henry Selick and their dedicated team of animators had hoped for. After the film left theaters, however, it began a transition from beloved cult movie to cultural phenomenon. Before long, Jack Skellington's grinning skull was everywhere from t-shirts to tattoos—and the story of how this creepy classic came about is just as interesting as the film itself.

The idea originated from a Burton poem

Burton originally penned the story of The Nightmare Before Christmas as a poem when he was a young man working as an animator for Disney—a role he never quite settled into, going as far as likening his time there to being stuck in a prison. Despite his education at the prestigious California Institute of the Arts, Burton could never adapt his own style to that preferred by Disney, something that became clear to him while working on 1981 feature The Fox and the Hound. "I couldn't draw those four-legged Disney foxes. I just couldn't do it," he later recalled. "I couldn't even fake the Disney style. Mine looked like roadkills."

After a brief run as a concept artist, Burton was ultimately deemed expendable, though he kept in touch with another animator struggling to adhere to the Disney way, Henry Selick. Burton shared his haunting poem about a skeletal figure named Jack Skellington with Selick, who showed immediate interest in directing a feature version. Beetlejuice co-writer Michael McDowell was enlisted to adapt the poem for the screen, and production started in 1991.

Disney developed the film, but distanced themselves from it

Having initially considered turning Burton's holiday themed poem into an '80s TV special or a short film similar to 1982's Vincent (also based on a Burton poem) only to back out, Disney relented as the decade came to a close. The success of 1988's Beetlejuice and 1990's Edward Scissorhands gave Burton enough negotiating power to arrange a developmental deal with Disney and the project was finally greenlit, with Burton acting as a go-between for the studio and his chosen director. After seeing the first trailer, however, then-chairman/CEO Michael Eisner decided that The Nightmare Before Christmas was just "too dark" for typical Disney audiences. The trailers were edited and the film was shifted to Touchstone Pictures, the distribution imprint Disney used for movies with the kind of adult-themed content they don't want associated with their child-friendly brand.

They still hid a Mickey in it

Despite Disney not wanting to associate themselves with it publicly, tribute was still paid to the Mouse House in The Nightmare Before Christmas in the form of a hidden Mickey. This decades-old tradition of subtly including Mickey Mouse in some shape or form in every Disney animated feature has never been acknowledged by the company, though that doesn't stop fans going over their films with a fine-toothed comb in search of this guaranteed Easter egg. While some films only get Mickey, however, others get more than one Disney legend making a sneaky appearance—like Nightmare, for instance. As the children of the world wake up on Christmas morning and find their presents to be a lot more terrifying than usual, a set of siblings can be seen sporting some unmistakably Disney pajamas: one set featuring Mickey, the other patterned with the face of Donald Duck.

It took more than three years to complete

Stop-motion animation may not look quite as smooth and silky as modern CGI, but the effort that went into making The Nightmare Before Christmas rivals anything Disney have done with Pixar in the years since. The film was shot at 24 frames per second, which meant that the characters had to be painstakingly re-positioned 24 times for every second of film. It took a whole week to create just a single minute of footage, with the entire process stretching out for more than three years.

It wasn't just a case of nudging a figurine slightly to the right, either. The characters themselves had to be carefully disassembled and reassembled for every frame so their facial expressions matched what was happening onscreen, with particular focus on getting Jack and Sally right. The Pumpkin King had more than 400 interchangeable heads, whereas his ragdoll love was designed with a series of masks that covered all the necessary emotions.

Oogie Boogie was the toughest character to design

Despite being a simple burlap sack filled with creepy crawlies, Nightmare's antagonist Oogie Boogie was actually the hardest character to create. Director Henry Selick admitted in an interview that visual consultant Rick Heinrichs had to intervene to re-sculpt the bulky boogeyman, with his demise in the film proving particularly tricky to navigate. The scene in which Oogie is fatally unraveled, spilling his insect insides everywhere, consisted of four shots that each took a full month to make.

The animators were not the only people to complain about Oogie Boogie, with many viewers feeling that Ken Page's portrayal of the villain verged on racist. Selick defended the character, insisting that Page modeled his voice performance on Cab Calloway in the old Betty Boop cartoons. This argument is supported by the fact that two lines of dialogue are lifted directly from 1933 Betty Boop cartoon The Old Man of the Mountain—and composer Danny Elfman has a long history of channelling Calloway, as he did in the film Forbidden Zone.

They started filming it without a completed script

The time-consuming nature of making a stop-motion feature meant that Selick and his team were keen to get started on making The Nightmare Before Christmas as soon as they humanly could, even if it meant doing so without a completed script. Production on the film began in San Francisco in 1991, when Selick had nothing but Burton's best wishes and a few songs to go on. "We had three songs by Danny Elfman but no real screenplay, and we had to start because we had a pretty tight budget, and had to finish the movie in time," he admitted. "So we started off with the song 'What's This?'"

In the end, Elfman's girlfriend at the time, Caroline Thompson, was brought in to help move the script along after Michael McDowell fell ill and was unable to complete it. Selick credits Thompson with "stitching the songs together" and making the film work as a complete piece.

Burton and Elfman fell out over Jack's voice

All of Jack Skellington's musical numbers in the final cut of The Nightmare Before Christmas were sung by Danny Elfman himself—that's Nightmare trivia 101. What not everybody knows is that the former Oingo Boingo frontman also recorded all of the Pumpkin King's speaking parts. While he nailed the singing as expected, Elfman's voice acting just wasn't up to Selick's standards, and in the end, he had to go to Burton with the issue. When the pair decided that they would have Chris Sarandon come in to re-record the scenes, Elfman's hurt feelings — as well as disagreements over scoring work for Batman Returns — caused him to decline to score Burton's next film, Ed Wood.

Despite having to share the credit for Jack Skellington, Elfman's contribution to Nightmare should never be understated. The world-renowned composer also gave his voice to Barrel, the smallest of Oogie Boogie's miniature henchmen, as well as the Clown with the Tear Away Face. In the end, his voice being in the movie just wasn't enough for Elfman, who had the animators create a shrunken version of his head and hide it inside a cello.

Burton was supposed to have his own cameo

Speaking of severed heads, Tim Burton's was also supposed to appear in the film during a brief shot in which three skating vampires play ice hockey on a frozen lake, but their makeshift puck was changed to a jack o'lantern at the last moment. The assumption is that Disney deemed the inclusion of their former employee's head a step too far and leaned on Selick to change it, though the original storyboard has since been released alongside a number of deleted scenes. The footage (narrated by Selick himself) also revealed that a number of other parts of the film were altered for the final cut, including Jack's attempts to discover the meaning of Christmas through a series of scientific experiments, which had a number of visual gags removed, and Oogie Boogie's dance, which was supposed to include a small scene created using cell animation but was eventually cut to help rein in the running time.

Oogie Boogie was Doctor Finkelstein in disguise in early versions

The biggest reveal from the unearthed early footage was a twist ending that was eventually removed for a more straightforward, but no less engrossing, climax. The storyboard in question details an alternate take on the moment that Jack rescues Sally from the burlap clutches of Oogie Boogie. When the boogeyman's sack starts to unravel, it isn't just worms and spiders that come spilling out—Doctor Finkelstein is in there too. His reason for kidnapping Sally is pure jealousy, taking her because, even though it was he who created her from "bits of flesh and scraps of cloth," she still chose Jack. A defiant Finkelstein goes on to call Jack an "oblivious twit" and explain that he wanted to "teach Sally a lesson" before declaring his intentions to make a new creation and disappearing through a trap door.

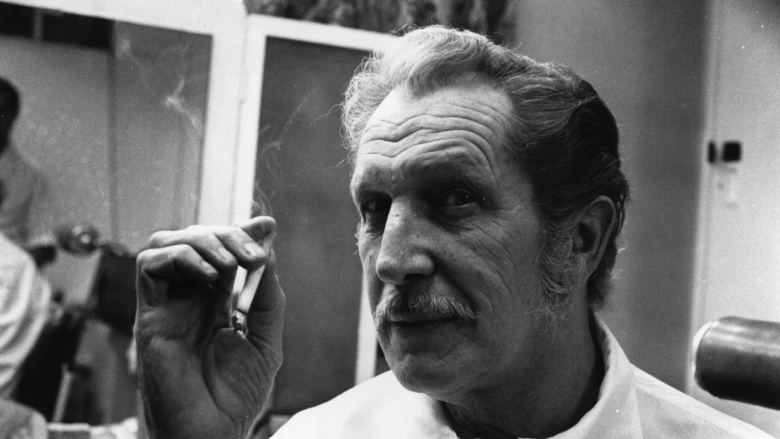

Vincent Price was supposed to voice Santa

Burton became a fan of Vincent Price at a young age, following his career closely and eventually managing to convince his idol to work with him on 1982's Vincent. This semi-autobiographical short delves into the somewhat disturbed mind of a seemingly normal suburban boy whose deepest desire is to be just like Vincent Price. Price narrated the five-minute film, and the pair worked together once more in 1990's Edward Scissorhands, in which the horror icon made his last screen appearance as the titular character's inventor, though their third collaboration had to be called off after Price's wife passed away.

Selick revealed that Price came into the studio to record his parts, which included the opening and closing monologues of the film, though the veteran actor was "despondent" after losing his wife and they were forced to consider alternatives. Burton and Selick met with Don Ameche, who was subsequently deemed too "grouchy" for Santa, and James Earl Jones had discussions with Elfman that ended in an angry shouting match. In the end, Ed Ivory, a relative unknown with no prior experience, was entrusted with the part.

The voice of Patrick Stewart was also cut

Easily the biggest actor to find his voice work cut from the final film, Patrick Stewart was brought onto Nightmare early on in its development, when Burton's original poem was supposed to play a bigger part in the narrative. The intention was to have Burton's words read at length over the course of the movie, and Stewart's unmistakable tones were considered perfect for the job. The Star Trek legend recorded a film-length adaptation of the poem (as well a rendition of Burton's original piece in its entirety) though as the story developed and the movie was reshaped, Stewart's parts were reduced to just the opening and closing monologues. In the end, it was decided that those verses would be better recited by the film's Santa, Ed Ivory, and the Stewart version ended up on the cutting room floor, and the film's official soundtrack.

Christopher Lee also recorded the poem

Another of Burton's horror heroes came in to do a reading of his original The Nightmare Before Christmas poem: Christopher Lee, whose definitive recording appeared as an extra on the collector's edition DVD. The pair quickly became friends, working together on a number of live-action and animated projects before Lee passed away in 2015 at the age of 93. Burton led the tributes, revealing just how influential Lee was on him and his career.

"Christopher has been an enormous inspiration to me my entire life. I had the honor and pleasure to work with him on five films," said Burton. "He was the last of his kind, a true legend who I'm fortunate to have called a friend. He will continue to inspire me and I'm sure countless others for generations to come."

Jack went on to have skeleton children

In the final cut of the film, the last that Jack and old Sandy Claws see of each other is when the latter, after saving Christmas and forgiving his counterpart for attempting to commandeer the holiday, flies over Halloween Town and gives the residents their first-ever snowfall. In an unused epilogue scene, however, Santa reveals that he actually visited his old friend Jack years after their holidays disastrously crossed paths, and found him with a handful of musically inclined children by his side.

"And though that one Christmas things got out of hand, I'm still rather fond of that skeleton man," recalled Santa. "So many years later I thought I'd drop in, and there was old Jack still looking quite thin, with four or five skeleton children at hand, playing strange little tunes in their xylophone band."

Burton quashed the idea of a sequel

Rumors about a sequel to The Nightmare Before Christmas being developed are nothing new, gathering pace every time a former cast member or colleague mentions the idea of a second film, only to inevitably come to nothing. One piece of gossip that turned out to be true, however, is that Disney considered making a second Nightmare film in the late '90s and early '00s, though they insisted that it be rendered with CGI this time around.

While Selick has always emphasized that a sequel would have to be stop-motion, Burton has been far less receptive to the idea of making a return to Halloween Town, stop-motion or otherwise: "I was always very protective of it, not to do sequels or things of that kind—you know, 'Jack Visits Thanksgiving World' or other kings of things," he explained. "Just because I felt the movie had a purity to it... it was important to keep that kind of purity of it."

Selick used Jack Skellington in later films

The fact that Burton had no intention of creating a The Nightmare Before Christmas sequel didn't stop Selick from returning to the character later. He gave him a cameo in 1996's James and the Giant Peach, and brought him out again for the 2009 stop-motion adaptation of Neil Gaiman's novel Coraline—a Burtonesque story following the plight of the titular child as she discovers a doorway to a sinister parallel world hidden in her new home.

The film evoked Nightmare in a number of ways, though those with a keen eye were able to spot a far more direct reference. As Coraline's mother cracks eggs over a bowl, Jack's grinning skull can be seen inside one of the dripping yolks—a blink-and-you'll-miss-it nod to the Pumpkin King.

There's already (sort of) a sequel...and a prequel

In the mid-2000s, Capcom released a video game called Oogie's Revenge, which takes place after the events of The Nightmare Before Christmas film. Jack gets bored with his life again, while Oogie is sewn back together by his trio of henchmen and the burlap sack decides he wants to be the king of all holidays, not just Halloween. The game ends pretty much identically to the film, with Oogie again defeated and Jack once again re-dedicated to his true calling of Halloween. (No one said it was a great story.)

And there's a video game prequel, too. The Pumpkin King, released at the same time as Oogie's Revenge, actually explains the huge gaps in the film's continuity. The conflict and jealousy between Jack and Oogie is explored, as well as why exactly Oogie has to live underground in his lair. Spoiler alert: it's because once again, he lost a fight with Jack.