The Untold Truth Of Steve Ditko

As you may have already heard, comic book artist Steve Ditko died at the age of 90. If you're a longtime comic book fan, you're already thinking about your favorite Ditko comics and characters. If you're not, however, you may be asking yourself who this Ditko guy was and why he was so important. Most stories mention that he co-created Spider-Man, which is no doubt a surprise to the many people who thought writer Stan Lee was solely responsible for that character. Ditko was never as famous as Lee, or even Jack Kirby. For that matter, he didn't want to be.

Steve Ditko was an unusual man with contentious relationships both to his most famous collaborators, and to the concept of fame itself. However, his impact on comics throughout the last four decades of the 20th Century should not be underestimated just because there are no interviews with him to read. Spider-Man was only one of the many enduring characters he created or co-created over his long career, and his innovative artist style stands out as fresh and unique even to this day. So let's take a look back at Steve Ditko, the man and his work.

A hero's humble beginings

Steve Ditko was born to a Slovakian-American family in Johnstown, Pennsylvania in 1927. As recounted in Blake Bell's book Strange and Stranger: The World of Steve Ditko, he grew up on comics. His dad was a fan of the classic newspaper strips like Prince Valiant, but young Steve really got excited when he discovered Batman and The Spirit as an adolescent. He was just barely too young to fight in World War II, but he joined the army after high school just the same, and drew comics for a military newspaper while serving in postwar Germany.

After he got out of the army in 1950, he found out that Jerry Robinson, his favorite Batman artist, taught at the School of Visual Arts in New York City, so he moved there and enrolled on the GI Bill. Robinson was impressed by Ditko's talent and dedication, and became his mentor. Robinson introduced him to Stan Lee while he was a student, and by 1955 Ditko was working at Atlas Comics (the precursor to Marvel) where Lee was an editor. For those first five years he mainly drew horror and sci-fi comics (the staples of 1950s Atlas). That's when he really developed his unique and dynamic style, full of small, nervous-looking figures in the midst of large and threatening worlds.

That friendly neighborhood wall-crawler

The exact story of how Spider-Man was created is the subject of some dispute. Stan Lee was the writer and editor when the webslinger first appeared in Amazing Fantasy #15, and originally took credit for the character. Jack Kirby was also involved at an early point, doing his own design for the costume that was ultimately abandoned and has since been lost to time. Elements of Kirby's work with Joe Simon on the Archie Comics superhero known as the Fly, and even an earlier unpublished Spider-Man comic, may have influenced the character.

What is clear, however, is that Steve Ditko created the unique look of Spider-Man and his world. The Spider-Man costume was unlike any worn by superheroes that came before. His face is totally covered, and the web-lines on the red parts of the costume make it busier than other outfits, which tend to be much simpler. The fact that nobody changed it to something easier to draw after Ditko left is a testament to how beautiful and iconic the costume is. Ditko's uniquely jittery style of drawing human figures also contributed to Spider-Man's iconography: the way his body contorts when swinging on a web, the way he crouches on rooftops, and the Hook-em Horns/heavy metal-esque thing he does with his hands to shoot webs.

The apex of Ditko's Amazing Spider-Man was #33, a story titled "The Final Chapter." Trapped under a huge fallen piece of machinery as water pours down from overhead, Spider-Man knows he must escape to save Aunt May's life. Rather than dismissing this feat of strength and rushing on to more action-packed scenes, Ditko spends pages on Spider-Man's struggle, making it the most triumphant moment of his career when he finally manages to victoriously lift that heavy machinery. It's unlike anything superhero comics had done before, and stands up to anything that came after. It was so influential, it was adapted into the Tom Holland-starring Spider-Man: Homecoming.

The psychedelic doctor

Doctor Strange, who first appeared in Strange Tales #110, was much more an undisputed Ditko co-creation, for which he's often credited with having the original idea itself. In any case, the idea of a sorcerer who helps normal people with mystical problems they can't comprehend is an idea as old as comics, if not older. It was Ditko's unique visuals that made Doctor Strange popular. As the Strange Tales run continued, the good doctor journeyed farther and farther outside the Earthly realm, until he was in totally abstract spaces full of uncanny shapes and no clear sense of up or down. Eventually he finds himself facing the fire-headed demon Dormammu in the realm of Eternity, a living figure made of stars and galaxies who's basically the Marvel Universe version of God.

These comics were hugely popular with college students of the 1960s, who often assumed Steve Ditko must be taking the same psychedelic drugs they were. In fact, this couldn't have been further from the truth, as Ditko was a political conservative and generally a very straight-laced guy, who never touched an illegal drug in his life. In a way this makes the visuals all the more impressive, because Ditko had this totally wild imagery, unlike anything seen before, in his totally unaltered mind.

Marvel's greatest armorer

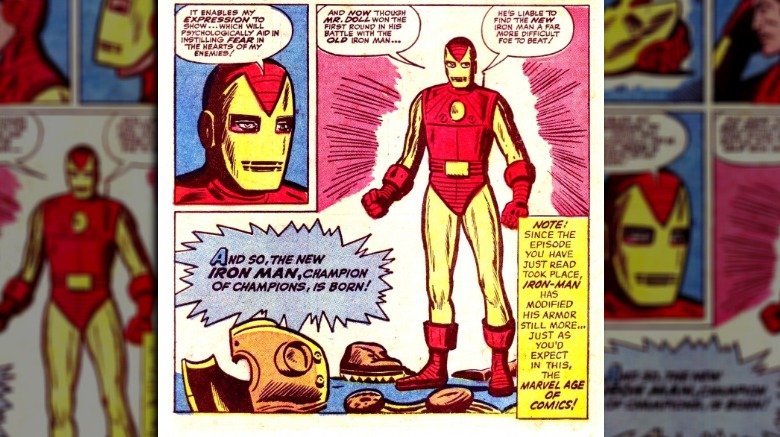

While he's primarily associated with Spider-Man and Strange, Steve Ditko also worked on other Marvel superheroes in those early days. He drew quite a few early Hulk stories, aiding the visual evolution of the Lee/Kirby creation. He also redesigned Iron Man to become the hero we all recognize by that name to this day. In the earliest Iron Man stories, he wore bulky armor with a bucket-like helmet, and it was all one color — originally gray, but switched to yellow/gold. In Tales of Suspense #48, however, Ditko replaced that armor with a much sleeker suit of red and yellow, featuring a yellow face mask on an otherwise red helmet, a red torso, and yellow arms and legs with red gloves and boots. Obviously the design evolved further over the next several decades, but nevertheless Ditko's Iron Man is immediately recognizable as the same guy from the recent Avengers movies, whereas Kirby's is not.

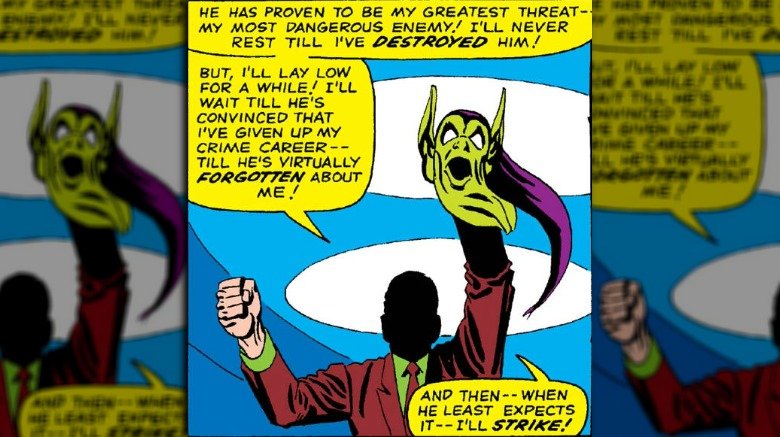

Mounting trouble in Spider Country

By 1965, Steve Ditko was receiving plotting credit on his Marvel comics, although Stan Lee was still writing the dialogue. Since Lee was also the editor, he ultimately still had control of the books as well as the company. He openly needled Ditko in an interview with the New York Herald Tribune that same year, saying, "Since Spidey got so popular, Ditko thinks he's the genius of the world."

The most common story about Ditko's last straw at Marvel is that he and Lee fought over the true identity of Spider-Man's enemy the Green Goblin, who Lee intended to be Peter Parker's best friend's father, while Ditko felt it should be an anonymous criminal. However, comics historian Brian Cronin has disputed that account. Whether it's true or not, Ditko and Lee were no longer speaking and Ditko had become increasingly socially isolated in general. He'd also become a devout follower of Objectivism, the philosophy espoused by novelist Ayn Rand. Like the hero of her book The Fountainhead, Ditko was unwilling to compromise with anyone on his artistic vision. That made him particularly incompatible with a dominant collaborator like Stan Lee, and Ditko left Marvel before the end of '65.

A new home and a new bug

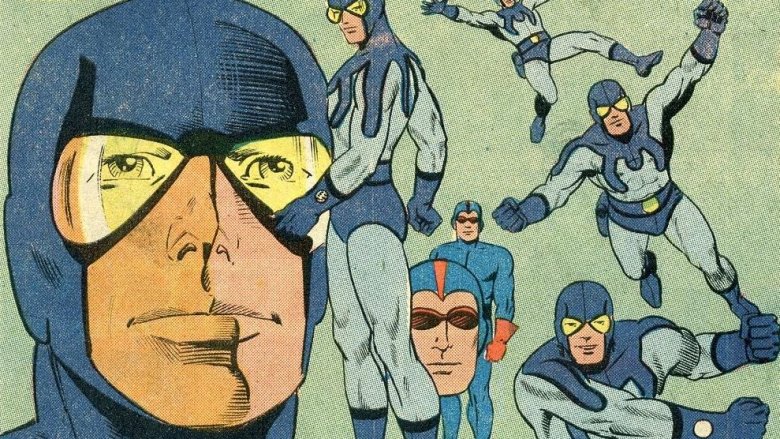

Charlton Comics was a much smaller pond, in which Steve Ditko would be a much bigger fish. He redesigned their most powerful superhero, Captain Atom, and gave him a new female partner, the shadow-powered superspy Nightshade. He then went on to create an entirely new version of the Blue Beetle. Whereas the previous Beetle, Dan Garrett, had superpowers thanks to a mystical Egyptian scarab, that artifact was lost with his death, leaving his young successor, Ted Kord, to honor Garrett's legacy as a non-powered tech-based superhero.

Ditko's Blue Beetle had a memorable costume design that recognizably shares an aesthetic with Spider-Man's without resembling it too closely. He carries a gun that shoots a flash of light that temporarily blinds his opponents, wears protective goggles, and travels around in a flying beetle-shaped airship. He also swings around on a grappling line, which is suggestive of Spider-Man — but also of Batman. If some of this, including carrying on the mantle of a Golden Age hero, sounds suspiciously similar to another, later superhero, we'll get to that momentarily.

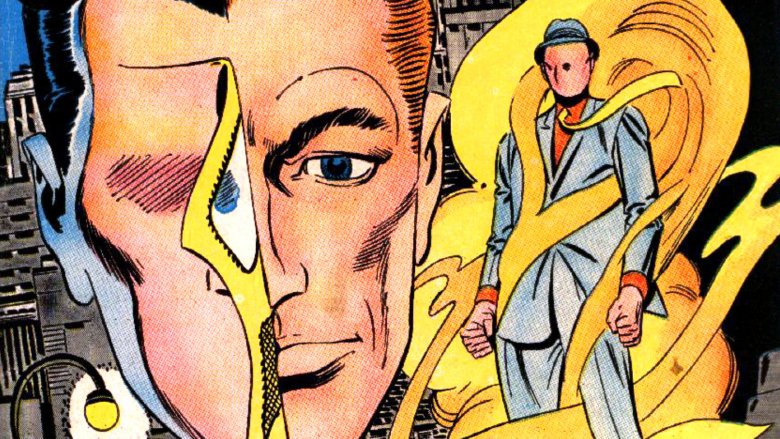

The man without a face

Steve Ditko's other important Charlton creation was an entirely original hero, and one with an enduring legacy of his own. The Question doesn't wear a superhero costume per se, just a distinctive suit and hat with a mask that makes it look like he has no face. In his daily life, he's reporter Victor Sage, who's totally devoted to the truth and the law. His worldview reflects Ditko's Objectivism, with a complete unwillingness to compromise and a strong dislike of chaos. He appeared in five issues of Blue Beetle, first as a back-up strip and then in a crossover in Blue Beetle #5. He starred in the one-shot Mysterious Suspense #1 before Charlton canceled their superhero line as Ditko departed in 1967.

Years later, Alan Moore would take inspiration from Ditko for his legendary 1986 series with Dave Gibbons: Watchmen. By then, Charlton was out of business, and DC Comics had bought the rights to their characters. Moore wanted to use them to tell a realistic and adult story about how dystopian a world with real superheroes might become, and he planned to use the Charlton heroes to do so. Ultimately, DC decided they wanted to incorporate those characters into their comic book universe instead, so Moore and Gibbons populated Watchmen with recognizable pastiches. The Question became Rorschach, Blue Beetle became Nite Owl, Captain Atom become Dr. Manhattan, and so on. Moore still acknowledges the influence of Ditko, however, and it's clear that without the Question, there would be no Rorschach. Without Steve Ditko, there could be no Watchmen.

Meanwhile, Blue Beetle, the Question, and Captain Atom all got their own DC Comics in the 1980s, and while Ditko wasn't involved, his influence was unmistakable. All of his Charlton creations still exist in the DC Universe in some form to this day. Ironically, in 2014 Grant Morrison and Frank Quitely created an homage to Watchmen called Pax Americana, as part of Morrison's multi-layered DC series Multiversity, and this time they used the original Charlton characters, creating a Captain Atom who resembled Dr. Manhattan even more closely, a Question who was more like Rorschach, and so forth. Comics, it has often been said, are cyclical.

Hawks, doves, and other shady creeps

Steve Ditko also worked directly for DC Comics several times over the course of his career. Although his work there is less world-changing than at Marvel or Charlton, he did create several enduring characters and concepts. The Creeper first appeared in Showcase #73. His secret identity as truth seeking reporter Jack Ryder is very similar to the Question's Vic Sage, but the Creeper is the opposite of the Question: he's a chaotic laughing weirdo who looks like an other-dimensional being even though he's really just Ryder in a creepy costume. He got his own series, Beware the Creeper, although it only ran for six issues, with Ditko departing halfway through the last one.

He also created the original Hawk and Dove for Showcase #75, two super-powered brothers who symbolize war and peace. Although the identities of the duo have shifted many times in the decades sense, Ditko's unique costume designs — all sharp jagged lines for Hawk and feathery scallops for Dove — have endured largely unchanged.

Ditko also launched Shade the Changing Man at DC in 1977, starring a character who evolved to be totally unrecognizable in the '90s Vertigo series by Peter Milligan and Chris Bachalo, although elements of Ditko's mythos were retained. Less notable DC Comics Ditko creations include the Prince Gavyn version of Starman and the sword and sorcery hero known as Stalker.

Letting his freaky anti-freak flag fly

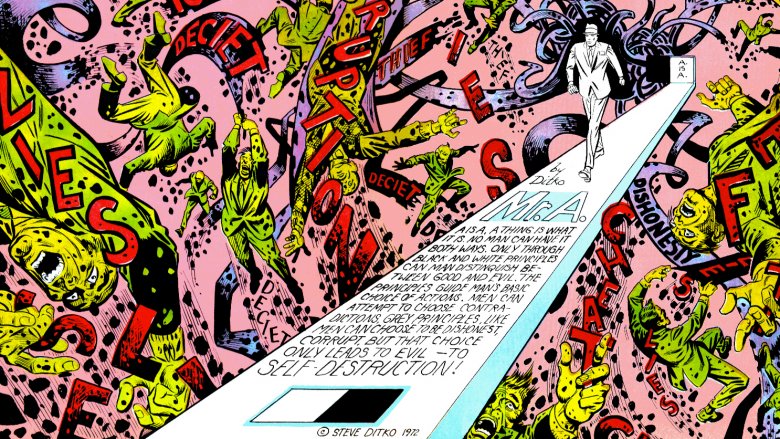

Even as he was working for DC in the late 1960s, Steve Ditko also began publishing independent comics, which gave him the opportunity to insert even more of his world view into the stories and also own them outright. His most famous creator-owned character is Mr. A, who first appeared in the underground anthology Witzend #3, and later had a few issues of his own title.

Mr. A was named for the Objectivist concept "A is A," meaning that nothing can ever be anything other than what it is. A man in a solid white suit and a white mask with a generic human face, Mr. A was more of a hardliner than even Hawk or the Question. In his first appearance, for example, Mr. A lets a teenaged criminal named Angel fall to his death rather than saving him. When the injured woman he's rescued from Angel accuses him of lacking mercy, Mr. A replies "I have no mercy or compassion for aggressors... only for their victims... for the innocent! To have any sympathy for a killer is an insult to their victims. Even if you weren't hurt... I wouldn't have saved Angel!"

As Ditko continued to draw Mr. A comics, they gradually abandoned conventional narratives to become illustrated comics essays championing Objectivist ideas.

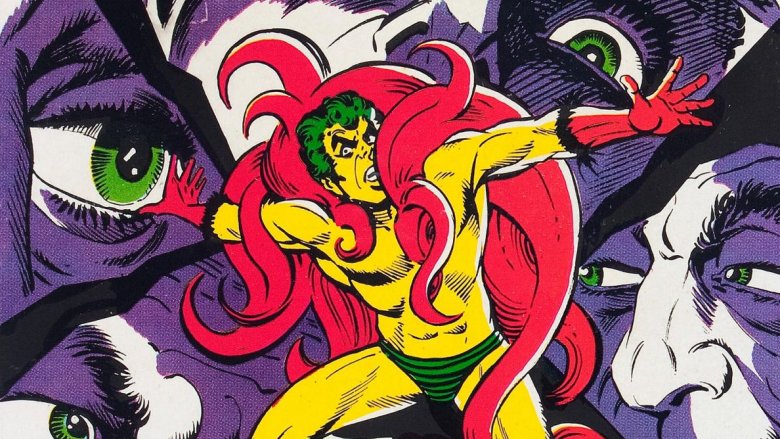

Bouncing back to Marvel

In time, Steve Ditko found himself back at Marvel, where his old nemesis Stan Lee was no longer involved in the day-to-day comics-making, although he remained the figurehead of the company. In 1988's Amazing Spider-Man Annual #22, Ditko and writer Roger Stern introduced Speedball, a character who reads as a clear effort to recapture some of the distinctive magic of 1960s Spider-Man. Like Peter Parker, Robbie Baldwin is introduced as a nerdy teen who acquires super powers in a science lab accident and becomes a hero with a unique costume and style of movement. Speedball doesn't swing from a thread; he bounces like a rubber ball, complete with immaterial multicolored spheres surrounding him when he uses his powers. Although the Speedball series, which was plotted and drawn by Ditko with scripts by Stern, only ran for 10 issues, the character went on to become a member of popular '90s superteam the New Warriors, and remains a lasting part of the Marvel Universe.

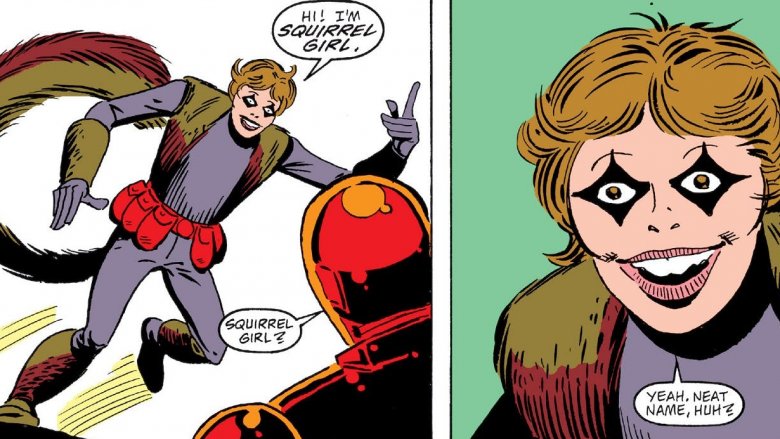

The heroine nobody saw coming

In 1991's Marvel Superheroes Vol. 2 #8, Steve Ditko and writer Will Murray created a character who nobody ever thought would be a big star — until she became one 23 years later. Squirrel Girl was introduced in a short Iron Man story. She's weird-looking and comes off as a bit of a loser, almost a parody of the kind of Marvel characters Ditko had seen introduced in the years since his original run in the '60s. Despite her strangeness and seemingly unimpressive power set, Squirrel Girl impresses Iron Man by defeating Doctor Doom with the help of — what else? — her army of squirrels.

Over sporadic appearances during the next couple of decades, it became a running joke that Squirrel Girl defeats villains that seem way out of her league, as she did with Doctor Doom in her first appearance. That's why, when she eventually got her own title by Ryan North and Erica Henderson, it was called The Unbeatable Squirrel Girl. North and Henderson remolded and reinvented the character. Under Ditko's pen, she seemed like a freak to be mocked. With North and Henderson, Squirrel Girl turned into a cute and likable protagonist who's now one of Marvel Comics' biggest stars. She'll soon by played by Milana Vayntrub in the FreeForm TV series of The New Warriors, alongside Calum Worthy as Speedball.

Never stop working, but only work for yourself

Steve Ditko's last work for a mainstream publisher was an Orion backup story he wrote in 1998, although it went unpublished for ten years, ultimately appearing in the Tales of the New Gods trade paperback. However, he never really retired. For the rest of his life, Ditko continued publishing zine-like indie comics, which were often little more than Objectivist propaganda, plus rants about the comic book industry and the state of the world in general. Even in this context, however, his dynamic artwork often shines. As recently as Fall 2017, Ditko and his friend and collaborator Robin Snyder launched a Kickstarter for a new Mr. A comic.

Ditko became more and more of a recluse over the years, gaining a reputation as "the J.D. Salinger of comics." He refused interviews and requests for collaboration, working only with Snyder and communicating with few others. Beyond that, few details of his later life are known. As The Hollywood Reporter put it when breaking the story of his passing, "Ditko is survived by his brother and a nephew. He is believed never to have married."

Although he never started a family of his own, his legacy is secured by the indomitable influence he had on the art form of comics books.