These Things Happen In Every Coen Brothers Movie

There are few directors who have a filmography quite like Joel and Ethan Coen. They've been nominated for over a dozen Academy Awards, and they've even won a few, including Best Original Screenplay, Best Adapted Screenplay, Best Director, and Best Picture.

Though most of their films could be loosely categorized as some flavor of "dark comedy," it's hard to overemphasize just how different each Coen brothers film is from all the rest. From the whimsical and colorful Hail, Caesar! to the dour and oppressive No Country for Old Men, from the broad slapstick of Raising Arizona to the slow and moody True Grit, time and again, the Coens have shown us that there's no type of movie they can't do.

That being said, when you watch your way through their entire filmography, you begin to realize just how many recurring themes, motifs, and story structures keep appearing again and again throughout the Coens' work. Between their fascination with crimes gone wrong, their uneasy relationship with the idea of religion, and their undeniable love for ordinary oddballs, join us as we run down the surprising ways that the many and varied films of the Coens are, in truth, far more similar than they might seem.

(Warning — there are spoilers below.)

The Coen brothers love an imperfect crime

Pretty much every Coen brothers movie starts the same way. A normal, unremarkable person living a normal, unremarkable life dreams of something more. In Raising Arizona, H.I. and Ed McDunnough want a child. In Burn After Reading, Linda Litzke wants plastic surgery. In The Man Who Wasn't There, Ed Crane wants to start a dry-cleaning business. But then, in order to achieve this dream, our small-town protagonist decides to commit a big-league crime. The McDunnoughs kidnap the child of a rich man. Linda tries to sell CIA secrets to the Russians. Ed blackmails his boss.

Sometimes, it's a bit less premeditated, and a chance to do the wrong thing just falls into our protagonist's lap. In A Serious Man, Larry Gopnik ends up in possession of an envelope full of cash that he doesn't know what to do with. In No Country for Old Men, Llewelyn Moss finds a suitcase full of money at a crime scene and decides to keep it. Sometimes, the "crime" our hero commits isn't even that bad. In Barton Fink, our titular protagonist is simply rude to his neighbor. And occasionally, it's the villains striking out on a misadvised caper. Tom Chaney foolishly kills his employer and then takes off running in True Grit, and the nihilists cook up a truly crazy scheme in The Big Lebowski. But all the same, at some point along the way, a character commits some sort of selfish act — an unforgivable sin — in order to get what they want, and from that point on, their fate is sealed.

The plan does not go according to plan

For a little while, things seem to be going smoothly with our hero's clever plan. But then, of course, something goes wrong. In Raising Arizona, H.I. and Ed's happily ever after with their ill-gotten son is cut short when two of H.I.'s old criminal buddies discover what they've done and decide to kidnap the kid for themselves. In Burn After Reading, Linda pressures her coworker, Chad, to sneak into the home of a CIA analyst to get some intel, and Chad ends up getting shot in the face. In The Man Who Wasn't There, Ed Crane's inept foray into blackmail ends up in a scuffle with his boss, who he winds up killing in semi-self-defense.

But for the ultimate example of just how bad things can get in a Coen brothers movie, look at Fargo. In this film, car salesman Jerry Lundegaard hires a pair of criminals to kidnap his wife so he can pressure her rich father into paying the ransom and then split the money with the kidnappers. But then, the crooks get pulled over by the police and end up killing a cop and two innocent bystanders in order to escape. So now, the cops are on their tail. Then, Jerry's father-in-law decides that he's going to deliver the money himself, which means that Jerry isn't going to get a chance to take his cut of the ransom, and the kidnappers are going to get all of it. And that's just the beginning. Things are still going to get much worse before the credits roll.

Karma hits like a hurricane

In a Coen brothers movie, whenever a character commits a crime or makes a major misstep, judgment rains down hard. But Coen movies aren't simple morality plays, where the evil are punished and the good are spared. It's not that simple. See, in a Coen brothers film, the worst punishments don't always go to the worst offenders.

By the end of Fargo, Jerry Lundegard's wife and father-in-law are both dead, as is one of the kidnappers, but Jerry himself and the other kidnapper get off far lighter, as they're simply arrested. In True Grit, Mattie does indeed get her revenge against the man who killed her father, but she also loses her arm along the way. The vain and selfish Linda survives Burn After Reading, but her two sweet and supportive co-workers do not. Donny, arguably the kindest character in all of The Big Lebowski, suddenly dies of a heart attack during the film's climax, while most other characters end up totally fine. In No Country for Old Men, pretty much everyone dies, including our protagonist, Llewelyn Moss, and at least a dozen or so people who cross the path of hitman Anton Chigurh. This also probably includes Llewelyn's wife, Carla, though her fate is admittedly somewhat ambiguous.

In the world of the Coens, it's not simply the case that if you give into temptation, you'll be punished, but if you resist temptation, you'll be okay. It's more like, when a person commits a sin, a storm of punishment comes down upon them and everyone around them. Some people will make it, and some won't, but who's left standing at the end often ends up being the result of dumb luck and not any sense of fairness or justice.

People don't change in the Coen brothers' movies

Most Hollywood films follow a pretty simple formula. At the beginning of the story, our hero is unhappy because they have a fatal personality flaw that they're unaware of. Then, their world is turned upside down, and they go on some sort of life-changing journey. By the end of the journey, our hero overcomes their flaw and evolves into a better and happier version of themselves. For some examples, pretty much all Pixar movies follow this basic structure.

This tried and true storytelling method, which is essentially ubiquitous throughout Hollywood films, is totally absent in nearly all Coen brothers movies. According to the Coens, people don't grow, and they don't change. Sometimes they live, sometimes they die, but that's about it. That's not to say that everyone in these films is bad. There are plenty of genuinely good characters in the Coens' films. But generally, the good characters stay good, and the bad ones stay bad.

The closest thing we can find to a proper character arc occurs in Miller's Crossing, and it's a depressing one. Midway through the film, kind-hearted mobster Tom Reagan decides to spare the life of a bookie named Bernie Bernbaum whom he's been ordered to kill. However, this act of kindness later comes back to haunt Tom when Bernie resurfaces and tries to blackmail him. In the end, Tom eventually tracks Bernie down again and kills him for real this time, and it's clear that this action has hardened Tom's heart forever. It's a pretty depressing lesson that Tom ends up learning from this experience, essentially "empathy will get you killed," but maybe that's the sort of lesson you need to learn if you're going to survive in the harsh world of the Coens.

Life is mysterious

A common quality among all the Coens' films that separates them from most other popular filmmakers is the way they handle the big questions in life. Most filmmakers just ask small- to medium-sized questions and then provide definitive answers to all the questions they ask. They'll make films that tackle issues like parenting, romantic relationships, or the idea that "with great power comes great responsibility."

What makes the Coens different is that every once in a while, they aren't afraid of asking the really big questions. What does it all mean? Is there a god? How are we supposed to live our lives? A Serious Man is definitely the film that tackles these issues most explicitly, but it's really all over their filmography. In the trippier parts of Barton Fink, No Country For Old Men, Inside Llewyn Davis, or The Big Lebowski, we sometimes feel like we're standing right on the edge of gaining some sort of profound insight into the human condition. A wise old cowboy played by Sam Elliott will stroll into the film and start to monologue, and we can tell that the film is trying to tell us something important, but wait, what exactly is it trying to say? Then, the movie will just sort of shrug, move on, and never really give us the answers we want.

When J.K. Simmons' unnamed character asks, "What did we learn, Palmer?'" at the end of Burn After Reading, he doesn't get a satisfying answer. Perhaps it would help him to hear the quote from the medieval rabbi and author Rashi that appears at the beginning of A Serious Man: "Receive with simplicity everything that happens to you." Or to quote the character of Clive from that same film, "Embrace the mystery."

Every character is memorable

There's an old saying in the world of theater, usually attributed to Konstantin Stanislavski, that goes, "There are no small parts, only small actors." Perhaps no filmmakers embody this philosophy quite like the Coens. As good as their protagonists are, their vast casts of supporting characters are often even better. Often played by total unknowns or quirky character actors who lack typical movie star good looks, these characters explode onto the screen as fully formed, highly specific human beings who are always instantly captivating.

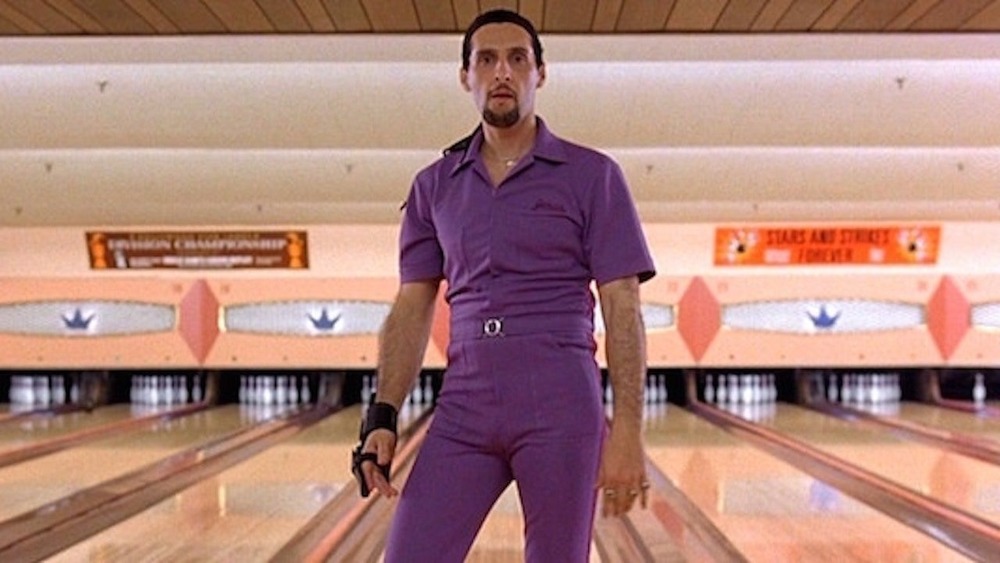

John Turturro's character of "the Jesus" in The Big Lebowski has just two brief appearances in the film, and he speaks only about five or six lines total, and yet he's completely unforgettable. When you think back on the film, you remember him as a major character, and yet he's barely in the movie at all and completely unrelated to the film's central plot. From the vast array of Midwestern locals who populate the world of Fargo to the strange assemblage of weirdo musicians that fill out the cast of Inside Llewyn Davis, from The Hudsucker Proxy's Buzz and Intolerable Cruelty's Wheezy Joe to A Serious Man's three rabbis and True Grit's man in the bear suit, no one crams more character into less screen time than the Coens.

The Coen brothers will repeat a line until it becomes a joke

If you pay close attention to their filmography, you'll notice the Coen brothers seem to utilize a fairly reliable formula for generating funny, quotable dialogue. They'll have a character, usually a minor supporting one, say a weird line of dialogue ... and then have them just keep repeating it. When Miller's Crossing Johnny Caspar makes reference to "the high hat" or when someone in O Brother, Where Art Thou? says "bona fide," at first it's just odd, and then it becomes a joke, and then at a certain point, it's almost a sort of mantra to ponder the deeper meaning of, like a Zen koan. (Or, if you will, a Zen Coen.)

One film that's absolutely jam-packed with these sorts of recurring lines is The Big Lebowski. Between the nihilists saying, "We believe in nothing," Walter snapping, "Donny, you're out of your element," and even the funeral director saying, "It is our most moderately priced receptacle," you might say that jokes like these "really tie the room together."

But the film where this technique is employed the most is probably Fargo. Carl Showalter's "I'm not going to debate you, Jerry," Norm's "I'll fix you some eggs," and Jerry Lundegaard's "real good now" are said so much that at some point, they lose all meaning. And all throughout the film, there's a single line that's repeated far more than any other, so much so that it's practically a part of the film's soundtrack, the ever-present, quintessentially midwestern "oh yah?"

You ask Stan Grossman, he'll tell you the same thing.

The cinematography is flawless

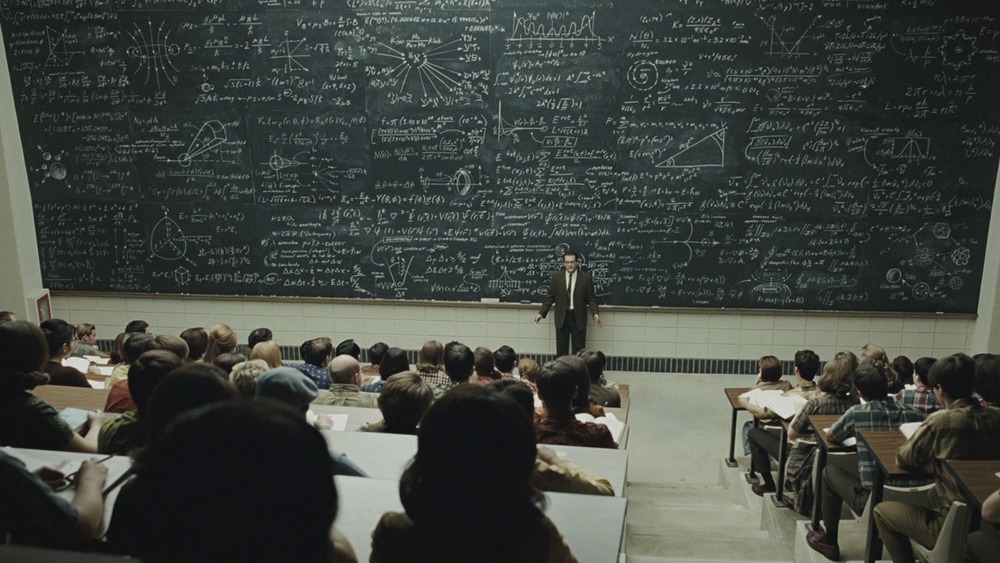

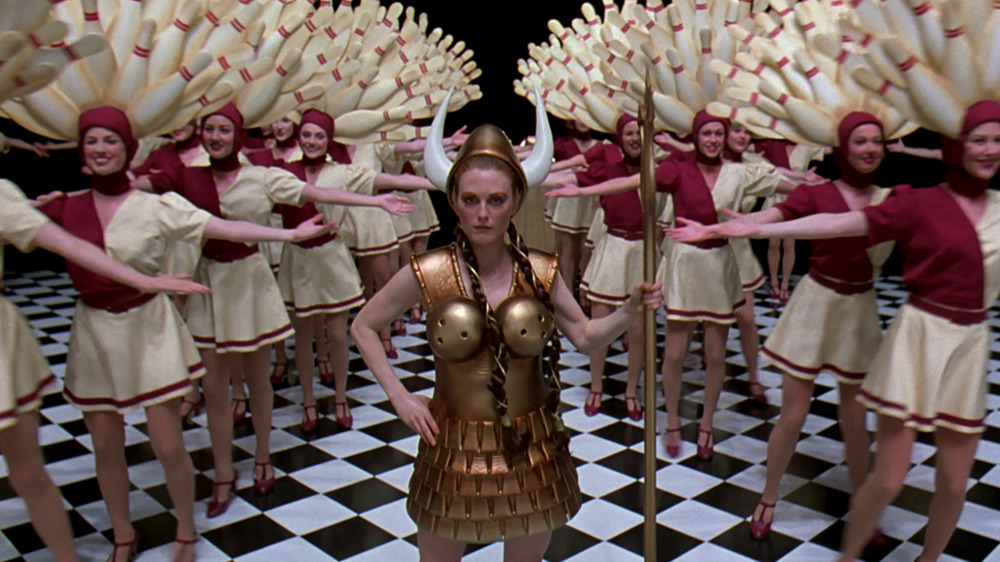

Given that the Coen brothers typically set their stories in rather mundane settings — like bowling alleys, hotels, and suburbs — you'd think that their films would just be all about the dialogue and wouldn't have much to offer in terms of visuals. However, one element of their films that's always surprisingly, jaw-droppingly good is the cinematography.

There are several different cinematographers that the Coens have worked with over the years, including Barry Sonnenfeld, Bruno Delbonnel, and Emmanuel Lubezki, but most of the time, the person responsible for transferring Joel and Ethan's vision to celluloid is cinematographer Roger Deakins. Deakins has collaborated with the Coens on 12 different films, and the visual language that he's helped establish for the Coens is instantly recognizable once you've seen a handful of their movies.

Deakins utilizes fairly standard shot/reverse shot coverage during conversation scenes, filmed relatively close up on the actors faces, but he also mixes in more experimental techniques in the scenes that are relatively dialogue free. Whether it's a super-wide lens establishing shot, a meticulously composed insert shot, or a full-on choreographed dance number, there are often sequences in a Coen brothers movie that feel more like an experimental art project or music video than a traditional narrative film. Through Deakins' lens, a dirty bowling alley can feel like heaven, an art deco hotel can feel like purgatory, and a perfect sunny suburb can feel like hell.

The Coen brothers like using the same familiar faces

There are many filmmakers out there who have favorite actors that they're fond of reusing again and again in their films. Wes Anderson has Owen Wilson and Bill Murray, Tim Burton has Johnny Depp and Helena Bonham Carter, and the Coen brothers have ... whoo boy, where to even begin?

Let's see if we can list all of the Coens' most frequent collaborators. Josh Brolin, J. K. Simmons, Richard Jenkins, and Holly Hunter all appear in three films each. John Turturro, Bruce Campbell, George Clooney, and Stephen Root all appear in four. And Jon Polito shows up in an impressive five films.

Steve Buscemi has roles in six films. He's Mink in Miller's Crossing, Chet in Barton Fink, the beatnik barman in The Hudsucker Proxy, Carl Showalter in Fargo, Donny in The Big Lebowski, and "the Tourist" in the Coens' installment of Paris, je t'aime. John Goodman also appears in six movies. He plays Gale Snoats in Raising Arizona, Charlie Meadows in Barton Fink, a newsreel announcer in The Hudsucker Proxy, Walter Sobchak in The Big Lebowski, Daniel Teague in O Brother, Where Art Thou?, and Roland Turner in Inside Llewyn Davis.

But without a doubt, the Coens' most frequent collaborator is Frances McDormand. She's Abby in Blood Simple, Dot in Raising Arizona, Marge Gunderson in Fargo, Doris in The Man Who Wasn't There, Linda Litzke in Burn After Reading, and C.C. Calhoun in Hail, Caesar! If that's not enough, she also has small uncredited roles in Barton Fink, Miller's Crossing, and The Hudsucker Proxy. That's nine appearances in Coen brothers films. Most directors don't even have nine films.

That strange Coen-ness will always be there

In many ways, the films of the Coen brothers are all quite different from one another. The time periods they're set in range from the Old West to the modern day to pretty much every decade in between. The tone of their films varies from the madcap and whimsical Raising Arizona and O Brother, Where Art Thou? to the somber and nihilistic No Country for Old Men and The Man Who Wasn't There. That being said, there's something in their films that always remains the same — a hilariously unsettling Coen-ness that's unlike anything else in mainstream film.

What if, in truth, their films aren't really all that different after all? Pretty much all of their movies are centered on America in the past hundred or so years, and all seem to be deconstructing the two most sacred institutions in American culture — money and God. Perhaps all their films are secretly both zany comedies and dark nihilistic dramas. It's just a matter of what's being emphasized.

There are jokes in No Country for Old Men that deliver laughs just as big as anything you'd find in The Big Lebowski. There's an odd darkness lurking just beneath the surface in O Brother, Where Art Thou? that's every bit as existentially terrifying as the absurd nihilism of A Serious Man. Perhaps that's the true spirit that unites all the films of the Coen brothers — a bleak and hilarious realization that chasing money will only lead to ruin, and if God exists, he is angry, unknowable, and probably doesn't like you.

Time and again, the Coens show us that in comedy there is darkness, in darkness there is comedy, and the American dream just might be the biggest joke of all.