Things Sci-Fi Movies Get Completely Wrong About Space

Movies have the power to transport audiences to places they'll likely never get to visit in their lifetime, and there's no destination more exotic than outer space. Escaping the confines of the little blue marble we call Earth is so difficult, dangerous, and expensive that, even 60 years after the first human space flight, only about 600 people have ever actually done it (via The New York Times). While the nascent space tourism industry will soon be sending many more of the world's super-rich into low orbit, most of us will only ever visit the final frontier through the vicarious experience of cinema.

Movies, of course, are rarely a perfect reflection of real life. The more uncommon an experience they depict, the more they can get away with fudging the details without shattering the audience's suspension of disbelief. Since outer space is a fantastical place for most viewers, filmmakers have license to indulge the fantasy, dramatize certain elements of life in space, and wholly invent others. Many films set in space are also set in the future (or in a galaxy far, far away), which allows for even further handwaving of modern-day scientific accuracy. There's nothing wrong with a movie prioritizing good storytelling over realism, but when certain inaccuracies are repeated often enough to become a genre convention, it can be a little misleading or even condescending to the general public.

Of course, no one gets more annoyed by unrealistic space movies than actual astronauts, astronomers, and space travel historians. Here are a few common mistakes about space that even the best sci-fi movies make, which experts want us Earthlings to know.

Space is silent

Let's get the obvious out of the way first: There's basically no sound in space. Humans perceive sound by picking up vibrations as they travel through molecules such as those in air or water (via Gizmodo). Without a medium to carry those vibrations, even an event as dramatic as an exploding space station would be silent to the human ear. There is sometimes enough interstellar gas and dust in space to carry some sound waves, but only on frequencies that are far too low to for us to hear.

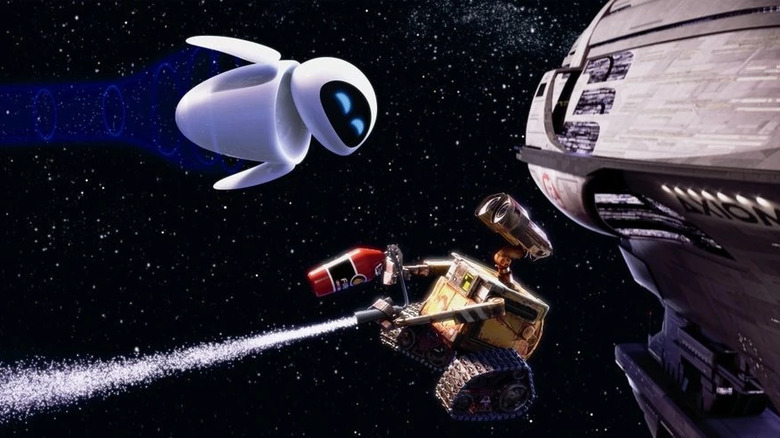

Of course, the laws of physics are no match for the magic of cinema, and many filmmakers have included sound in their space action sequences regardless of the real-life limitations. And frankly, we're not complaining. Sound is a key part of cinematic storytelling, and many of our favorite scenes set in space would be much less exciting without it. Just imagine the Death Star trench run from the original "Star Wars" without the "pew pew" of blasters or the roar of TIE Fighter engines, or WALL-E and Eve's dance through space without their adorable robotic vocalizations. Fun fact: Both of these films owe their distinctive soundscapes to legendary sound designer Ben Burtt (via SkySound).

On the other hand, silence can also be a powerful storytelling tool, which enhances the otherworldly mystery of outer space and provides an eerie contrast between the action occurring on screen and the sounds you'd expect to hear if they took place on Earth. For example, the space disaster at the opening of "Gravity" is all the more affecting because the only diegetic sounds are the voices and labored breathing of the astronauts in danger. However, in a video for Vanity Fair, Veteran Canadian astronaut Chris Hadfield explains how the sounds generated from inside one's spacesuit are the only things that a person on a spacewalk could possibly hear.

The planets are rarely in alignment

In a space sci-fi movie, a filmmaker might choose to indicate that a spacecraft is making its way towards or away from Earth by having it pass by the other familiar planets in our solar system. Using these landmarks in a story can create a sense of progress or anticipation — if a ship from Earth has made it all the way to Saturn, then you know it's traveled a great distance, and if an aggressive alien ship travels sunward past Mars, it means the Earth is in imminent danger. The opening of the 1997 film "Contact" takes the viewer backwards past each of the planets in our solar system and beyond in order to convey the unfathomable scale of the universe.

It is, however, incredibly unlikely that any journey to or from Earth would take you close to any other planets in our solar system at all, much less all of them. While all eight major planets in our solar system have relatively similar orbital planes, their orbits line up only on very rare occasions. Earth and its closest neighbor, Mars, come into alignment once every 780 days (via Space.com). Unless a traveler were making their way towards Earth from the outer solar system close to that particular time, they'd be unlikely to come anywhere near to Mars. And the more planets they plan to visit along the way, the more carefully they'd have to plan their trip. After all, the eight planets in our solar system all share the same heliocentric longitude only once about every 396 billion years, which is a time frame that even the endless possibilities of movies don't want to consider (via Sky & Telescope).

Asteroids are very, very far apart

The vacuum of space is one of the most dangerous places a person can visit, but a big black emptiness is not necessarily the most visually interesting threat to convey on screen. This is particularly true if you're trying to tell an adventure story about a character for whom outer space is old hat. Rather than simply having your hero fly in a straight line through nothing for millions of miles, you might place some sort of dramatic space obstacle in their path, such as an asteroid belt. Movies like "The Empire Strikes Back," "Green Lantern," and "Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2" depict asteroid fields as cramped, chaotic areas of space that require expert piloting to navigate. In film, asteroids are close together and constantly in danger of colliding with each other.

In reality, asteroid belts like the one that circles our own solar system between Mars and Jupiter aren't dense at all, and spacecraft traversing it face practically zero risk of collision. According to Scientific American, the average distance between asteroids in our asteroid belt is several million kilometers. That's so far apart that it's impossible to see one asteroid from the surface of another without the aid of a telescope. Astronomers calculate that a collision between two reasonably sized asteroids (larger than 1 kilometer in diameter) should only happen about once every few billion years. Even hitting an asteroid on purpose is extremely difficult, as NASA scientists learned while planning the trajectory of the Galileo space probe's journey to Jupiter in the late 1980s.

It takes a long time to put on a spacesuit

In Ridley Scott's 2015 film "The Martian," astronaut Mark Watney (Matt Damon) is stranded alone on the red planet. During his efforts to farm his own food on Mars and communicate with Earth, Watney frequently pops in and out of his air-tight habitat and takes on and off his futuristic spacesuit, sometimes several times a day.

Michael Lye, the NASA coordinator at the Rhode Island School of Design, told SYFY WIRE that's nonsense. Not only is donning a spacesuit a time-consuming affair, but astronauts go through exhaustive systems and checks every time they prepare for any extra-vehicular activities (a.k.a EVA). Veteran NASA astronaut Nicole Stott explained to WIRED that astronauts perform what they call a "glove check" before going out and once every hour during an EVA to make sure their suits' integrity hasn't been compromised.

When an astronaut gets dressed for a spacewalk, they want to stay in their suit for as long as possible to avoid the time and effort of getting dressed up again. According to NASA, spacewalks outside the International Space Station lasts between five and eight hours, which is one of the reasons why — unlike what we see in "Gravity" — spacesuits include an adult diaper (via Space.com)

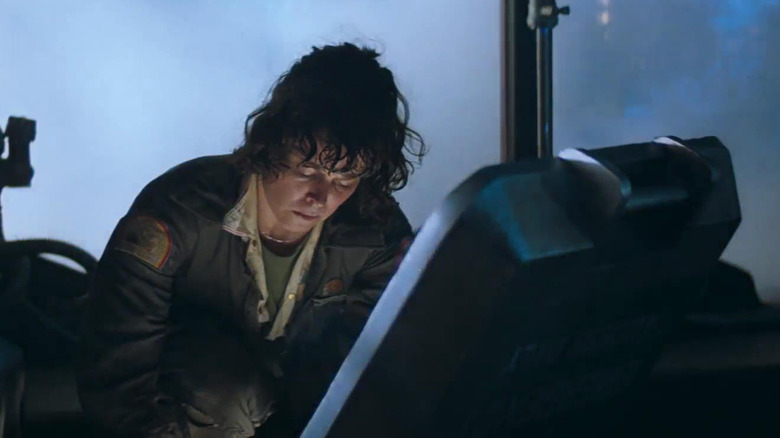

Dr. Cathleen Lewis, curator of International Space Programs and Spacesuits at the National Air and Space Museum, pointed out to GQ the ease with which "Alien's" Ellen Ripley slips into a pressure suit, which ignores safety protocols, including pre-breathing oxygen. This is a customary process in which an astronaut attempts to purge all the nitrogen from their bodies to avoid getting the bends during their walk. (via European Space Agency).

Real space helmets are small and sturdy

In 2022, GQ asked spacesuit expert Dr. Cathleen Lewis to critique the outdoor apparel used by fictional astronauts on-screen. While Dr. Lewis was pretty forgiving of the creative license employed by filmmakers and costume designers, there was one common criticism that applied to nearly every fictional spacesuit she's seen: The helmets — particularly the helmets' visors — are much larger than they need to be. Real astronaut helmets are designed to give the wearer the best possible protection and outward visibility.

In a movie, it's more important to be able to see into the helmet so that the audience can enjoy the actor's performance, which requires a larger visor. This is also why movie space helmets have lighting elements on the inside, which may help us see the face of the wearer, but according to Dr. Lewis, would create a lot of glare and make it very difficult for a real astronaut to do their job.

It's also common for a sci-fi movie to add suspense to a scene by having an astronaut's space helmet suffer a crack, usually in its transparent visor (see "Interstellar," "Ad Astra," and "Star Trek Into Darkness" for reference). It's a great visual device, as a helpless astronaut can only watch in horror as a crack expands, and try to rush to safety before the atmosphere inside the helmet is compromised. Real space helmets, however, are designed not to do this. They're made of highly strengthened polycarbonate and are incredibly difficult to damage (via NASA).

Decompression is deadly, but not dramatic

What makes outer space such an intriguing setting for films is that it provides an instant, built-in threat. Space is a deadly vacuum, and exposure to it can kill a person very quickly. This danger of decompression is real, but the way it's depicted on-screen is often an exaggeration of the truth in one way or another.

In 2000's "Mission to Mars," astronaut Woody Blake (Tim Robbins) removes his space helmet to dissuade his shipmates from mounting a dangerous rescue mission. When Blake unlatches his helmet, he is instantly desiccated. Astronaut Nicole Stott explained to Wired that this is both quicker and less painless than what would really happen. First, your bodily fluids will escape in a way that feels like they're boiling off of you, and then you will freeze ... but not before suffocating first. On the other hand, "Total Recall" — in which Arnold Schwarzenegger's eyes pop halfway out of his head — and "Event Horizon" — in which Jack Noseworthy gushes blood from his face — are both exaggerations of real-life decompression body horror.

In actuality, a human being exposed to a vacuum remains conscious for the 10 to 15 seconds that it takes for their body to finish circulating their last gasp of oxygenated blood (via Gizmodo). Any area of moisture exposed to space will freeze, and moisture beneath the skin will evaporate. It's not a pretty picture, but for 90 seconds, there's actually still a chance of reviving a compromised astronaut with minimal permanent harm. It's only after about two full minutes of exposure to a vacuum that a person's blood will actually start boiling, after which any hope of recovery is lost.

Firey explosions in space are very brief

Hollywood loves explosions, and filmmakers rarely allow silly things like physics or realism stop them from wowing audiences with a bright, loud "bang!" In fact, most explosions you see in action movies don't actually resemble their counterparts in real life. Actual bombs and grenades are designed to destroy, not to look cool, which usually results in a very brief, bright blast, a billow of dense smoke, and a concussive shock wave through the surrounding air. By and large, explosions in movies are longer, brighter, and involve a lot of red and yellow flames. Audiences are so used to measuring the power of an explosion by the standards set in films that the real thing looks underwhelming by comparison.

When it comes to outer space, the reality of explosions is even further from what we've come to expect based on movies and television (via Science ABC). Fire requires oxygen (or another oxidizer) to burn, and space is an airless vacuum. If a spaceship were to explode, there might be a brief burst of flames, but only long enough to burn away whatever oxidizers the vessel had packed with it in its atmosphere or fuel, which would take almost no time at all.

Explosions in space also don't cause shockwaves, for the same reason that they don't carry sound: There's no medium through which to carry it. Instead, space explosions represent a different sort of danger altogether in that the debris they create never slows down unless it hits something. A destroyed spacecraft shouldn't disappear in a bright fiery ball, but rather would keep hurtling forward forever as it flies apart.

Gravity doesn't have an on/off switch

Part of the appeal of traveling to outer space is experiencing the weightlessness of zero gravity, which can only be replicated on Earth for short periods and at great expense (via Space.com). However, sci-fi movies set in space usually don't show characters spending extensive time in Zero-G environments. This is because long journeys without gravity can be hazardous to an astronaut's health (via NASA), and also because shooting an entire movie with actors and props suspended on wires and gimbals is costly and annoying (via NBC). Instead, cinematic spaceships are often equipped with artificial gravity, so that scenes can be staged without the constant involvement of special effects.

Plenty of sci-fi films accept artificial gravity as a given of futuristic technology, and it's shown as a system that can be toggled on and off, as demonstrated in "Guardians of the Galaxy" or "Passengers." There are actually a few theories as to how sustained artificial gravity might be practical, but none of them involve going immediately from 0 to 1 Gs or vice-versa.

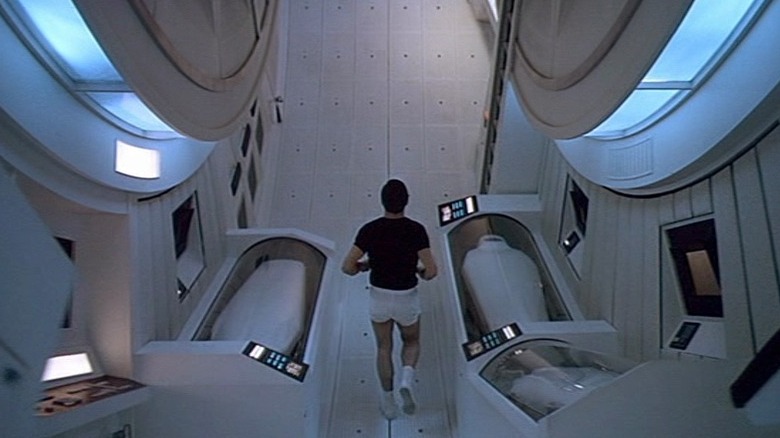

The most commonly depicted method of realistic artificial gravity uses centrifugal force to replicate Earth's gravity on its interior surface, as seen in "2001: A Space Odyssey" and "Interstellar." However, centrifugal force would require time to either speed up or slow down in order to increase or decrease the feeling of gravity, as astronaut Chris Hadfield explained to Vanity Fair. For this reason, it wouldn't be possible to simply turn artificial gravity on or off in a rotating ship like the one in "Passengers" or other sci-fi titles that show spaceships in a similar way.

Interstellar communication involves a lot of waiting

Space travelers both real and fictional depend on the ability to rapidly communicate with their home planet. Wireless communication signals travel much faster than any known physical object, but they're still confined within the universal speed limit of 186,000 miles per second or the speed of light (via NASA). In the history of space travel, the farthest any human being has traveled from Earth is 248,655 miles, which was achieved by NASA's Apollo 13 crew in 1970 (via Space.com). This means that in this extreme case, astronauts had to wait for about a second and a half to receive a message sent from Earth.

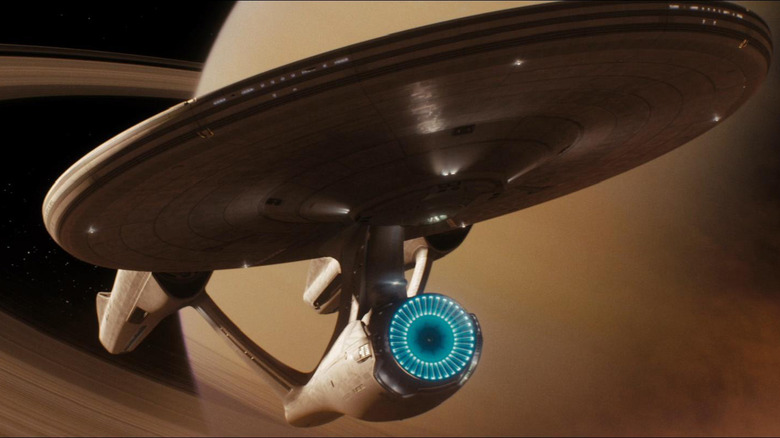

However, science fiction stories set in space frequently show astronauts communicating over much, much greater distances than any real person has ever traveled. In many sci-fi universes that include faster-than-light travel such as "Star Trek" or "Star Wars," it's also considered a given that far-flung planets and spacecraft will have the ability to communicate in real time. This is practically as far-fetched as warp drive.

Consider that even when close neighbors Earth and Mars are at their most proximal — about 35 million miles apart — it would take about four minutes to send a signal from one planet to another. Imagine this degree of latency applied to conversations between parties light years apart, and any sort of interstellar communication becomes totally unfeasible.

Some sci-fi films, however, embrace the difficulty of interstellar communications to increase narrative tension. For example, the crew of the Nostromo in "Alien" can't second-guess their orders to land on a dangerous planet because waiting for a reply would mean adding years to their journey.

Real spaceships don't have a self-destruct button on board

If you only knew space travel from its depiction in movies, you might imagine that every space vessel comes equipped with a "self-destruct" switch that the commander can use to detonate an onboard explosive in the event of a crisis. Ellen Ripley uses the Nostromo's self-destruct function to try to kill the xenomorph in "Alien," Kirk defeats a Klingon boarding party using the Enterprise's self-destruct in "Star Trek III: The Search for Spock," and Dark Helmet discovers that his ship's self-destruct is down for maintenance in "Spaceballs."

Astronaut Nicole Stott explained to Wired that no such switch exists aboard any of NASA's spacecraft, and it's hard to imagine a scenario in which one would be necessary while in space. The range safety crew at mission control on Earth, however, does have the means to remotely destroy a spacecraft in the event that a launch should go dramatically off course and accidentally become a surface-bound missile. Rather than risk a falling spacecraft crash-landing in a populated area, a member of the ground team can flip a switch and, as Stott puts it, "terminate the flight" in explosive fashion, sacrificing the astronauts to save civilian lives below. A US Air Force officer manned this switch during the first two minutes of every launch during the space shuttle program, in case something should go terribly wrong (via NASA). Thankfully, NASA has never had cause to execute this extreme security measure.