Film Adaptations That Have (Almost) Nothing To Do With Their Source Material

Adapting an existing work into a film is tricky business. While an original script lives or dies on its own merits, a movie adapted from a novel, short story, comic book, or other medium has to live up to its source material to some degree while also delivering a satisfying moviegoing experience. The screenwriter and/or director can take two paths: either use the source material as a launching pad and deliver a new story that sets its own course, or remain faithful to the original text.

Both approaches have their pluses and minuses — Universal's 1931 adaptation of Mary Shelley's "Frankenstein" has very little to do with the novel but remains a horror classic, while Frank Darabont's close read of "The Shawshank Redemption" pleased viewers who had never heard of Stephen King's novella as well as those who considered it a favorite.

There's no scorecard to determine which approach has worked best: faithful and far-ranging adaptations have succeeded or flopped in equal measure over the years. We can, however, measure some of the most extreme adaptations of page to film: those which left much of the original material in the dust and followed their own path. Following is a list of those film adaptations that had little to (almost) nothing to do with their source material.

The James Bond film series

If MGM's long-running James Bond film franchise has you curious to check out the novels by Ian Fleming on which they're based, be prepared to find very few similarities between the two. The early Bond films starring Sean Connery bear a passing resemblance to their source material, though there are still many changes in terms of plot and character (SPECTRE, not SMERSH, is the dominant bad guy organization). The Bond novels also feature less cheeky humor and more adult-minded material than was allowable on screen at the time (Goldfinger's gold passion is more, ahem, complicated in Fleming's book).

By the time Roger Moore took over as 007, the books only served as a reference point: in 1974's "The Man with the Golden Gun," the connections boiled down to character names and minor plot details. From 1981's "For Your Eyes Only" to 1989's "License to Kill," Eon Productions began to rely on fragments of short stories, elements from John Gardner and Raymond Benson's Bond novels, and unused plot points from Fleming's books. By the time Pierce Brosnan had taken up the Walther PPK to play Bond, the movies were almost entirely new creations, with only minor references to details from Fleming's novels or related books (like Kingsley Amis's "Colonel Sun"). Eon was mostly faithful to Fleming's "Casino Royale" for Daniel Craig's debut as Bond, but his subsequent adventures were original stories (even "Quantum of Solace," which borrowed just the name of a Fleming/Bond short story).

Cocaine Bear

Elizabeth Banks' gory, crowd-pleasing horror-comedy "Cocaine Bear" is indeed based on a true story: a bear did, in fact, discover and consume a batch of cocaine that had been dropped from a plane in December 1985. The beginning of the film follows what is the accepted theory of how the bear got the cocaine: the drug was being transported via plane by former corrections officer turned drug smuggler Andrew Thornton, who was believed to have tossed out some of the stash when he suspected that federal agents were tailing him. Thornton later parachuted out of the plane but was found dead in a driveway in Knoxville, Tennessee with approximately $15 million in cocaine strapped to his body.

However, the abandoned cocaine did not send the real bear into a murderous frenzy, as seen in the film. It actually killed the animal, which was found dead in the mountains of Fannin County, Georgia with 40 opened plastic containers carrying traces of cocaine. The Associated Press later reported that an autopsy performed on the bear's remains found three or four grams of the drug in its bloodstream, though it may have consumed more.

Ed Wood

After decades of dismissal as one of the world's worst filmmakers, writer-director Edward D. Wood, Jr., earned something like redemption with the 1994 biopic "Ed Wood." The film, directed by Tim Burton and written by Scott Alexander and Larry Karaszewski, depicts its namesake as a starry-eyed dreamer whose desire to make movies was hampered only by his lack of technical ability. The film touched on the major milestones in Wood's life and career — his friendship with a down-on-his-luck Bela Lugosi, the ramshackle production of his best-known film, "Plan 9 from Outer Space" — and his relationship with various eccentrics like TV psychic Criswell (played by Jeffrey Jones), horror host Vampira (Lisa Marie) and wrestler Tor Johnson (George "The Animal" Steele), as well as his penchant for cross-dressing.

Karaszewski later said that the film takes a sunny approach to Wood's life, which was often marked by personal turmoil that affected those around him. Wood's biographer, Rudolph Grey, noted in "Nightmare of Ecstasy" that the filmmaker struggled with alcoholism throughout his life, which upended his relationship with actress Dolores Fuller (the film blames their breakup on his cross-dressing) and resulted in physical violence with his second wife, Kathy Wood. The film also fictionalized elements of Lugosi's personality; though Martin Landau won an Oscar for his performance, various sources, including Lugosi's own son, decried the film's depiction of a foul-mouthed crank jealous of co-star Boris Karloff's success.

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre

The acts of depravity committed by Wisconsin murderer Ed Gein have inspired numerous horror films, including Alfred Hitchcock's "Psycho," "The Silence of the Lambs," and Tobe Hooper's "The Texas Chain Saw Massacre." However, the connection between Gein's crimes and these films is only relegated to a few details. Gein's obsession with his abusive mother and his decision to preserve the rooms in which she lived are the only elements shared between the case and "Psycho"; Gein did not wear women's clothing or keep his mother's corpse in his home like Norman Bates. Buffalo Bill's crimes in "Lambs" draw more on acts committed by other killers like Ted Bundy; Bill's connection to Gein is relegated solely to the body suit both created from women's skin.

"Chain Saw" and its many sequels and reboots are often cited as inspired by Gein's crimes, but the connection is largely through production design. Both Gein and the " Chain Saw" family constructed furniture and household objects from body parts: the farmhouse owned by Hooper's killers is adorned with furniture and objects made from human remains like those found in Gein's home, and Leatherface's trademark — a mask apparently made from human skin — echoes the face coverings that Gein culled from corpses. "Chain Saw" draws nothing else from Gein; even the clan's cannibal appetite is a construct from Hooper and co-writer Kim Henkel. No evidence ever confirmed that Gein consumed any parts of his victims.

The Mask

When Dark Horse Comics approached New Line Cinema about adapting its title "The Mask" into a feature, the studio envisioned the property as a replacement of sorts for its then-faltering "Nightmare on Elm Street" franchise. Though this sounds like a wild exaggeration, the idea of a horror "Mask" actually hewed closer to the source material than Chuck Russell's film. The Dark Horse "Mask" was a violence-steeped title in which the titular object transformed the hapless Stanley Ipkiss into an adrenalized psychopath who slaughtered everyone who opposed him. The entity within the Mask — dubbed "Big Head" in the comic — caused untold death and destruction for an array of unlucky owners (Ipkiss was killed in the first five-issue series), which included, at various times, DC Comics' Joker and Lobo.

In a 2017 interview, Russell said that New Line's original idea for "The Mask" was too reminiscent of Freddy Krueger. Given that the "Elm Street" formula of a wisecracking killer was on the wane, Russell and writer Mike Werb opted for a lighter, PG-13 take. This meant applying a cartoonish approach to any violence — with no body count — and making Ipkiss more lovable loser than misfit. The "Big Head" aspect of the Mask was also dropped, as were the series' disturbing villains, like the brutal mob enforcer Walter and the fascist Mask Hunters organization. What remained was essentially the Mask and its transformative powers.

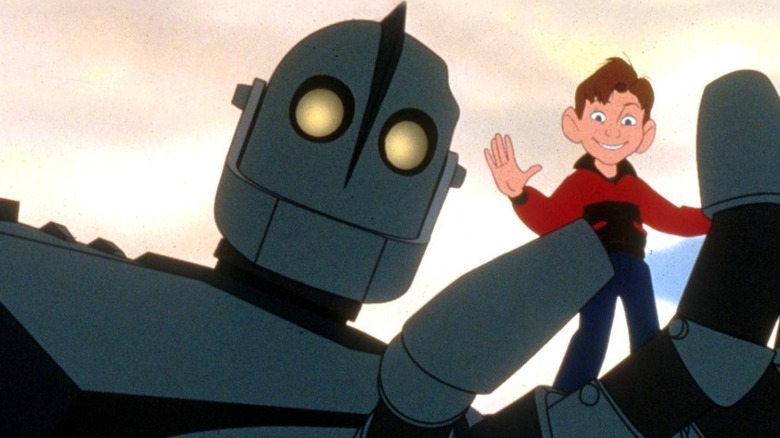

The Iron Giant

Though not a box office winner when released in 1999, Brad Bird's animated feature "The Iron Giant" has become a beloved title thanks to its heartfelt examination of loss and redemption, plus its mix of traditional and computer animation. The script by Bird and future "Smallville" writer Tim McCanlies is credited as an adaptation of Ted Hughes' 1968 novel "The Iron Man" (which was retitled in the United States to avoid confusion with the Marvel Comics character), but it actually uses very little of Hughes' story.

In fact, the elements shared between the movie and the novel boil down to the Iron Giant and his relationship with a boy named Hogarth. In Hughes' story, the Giant has no back story, while the film postulates that he's from space. There are no scenes involving Hogarth teaching the giant about death and heroism, and the primary conflict in the book doesn't pit the Giant against the U.S. military; instead, it fights an extraterrestrial monster called the "Space-Bat-Angel-Dragon," which demands that humankind feed it or face destruction.

Rock legend Pete Townshend released a 1989 concept album called "The Iron Man: The Musical" which hews much closer to Hughes' story. Townshend brought the project to Warner Bros. in hopes of turning his record into an animated feature; he later retained executive producer credit on "The Iron Giant."

I, Robot

Isaac Asimov's "I, Robot" is a collection of short stories penned between 1940 and 1950 that form a sort of composite novel, known as a "fixup." The stories present a world in which robots have gained sentience and even independence, putting them in conflict with the "Three Laws of Robotics," which force them to obey humanity. Asimov's stories are hugely influential in science fiction history, with the Laws referenced in numerous other novels, television series ("Doctor Who"), and movies ("Aliens"). They also appeared to serve as the inspiration for Alex Proyas's 2004 film "I, Robot," but the connection between them is tenuous at best.

"I, Robot" does feature Dr. Susan Calvin, a character that recurs throughout Asimov's stories, as well as his Three Laws of Robotics, and a robot (brought to life through voice and motion capture by Alan Tudyk) suspected of breaking one of those laws by killing his creator. Beyond those elements, it exists almost entirely outside of the "I, Robot" stories, largely because the film is actually based on an original script by Jeff Vintar – though as some observers have noted, it does resemble aspects of Asimov's unrelated novel "The Caves of Steel." When Fox bought the rights to Asimov's stories, it added Calvin and the Laws to the existing script while explaining the differences from the source material by stating that the film was "suggested" by Asimov's stories.

The Lawnmower Man

The 1994 science fiction thriller "The Lawnmower Man" sits high on the long list of the most misbegotten film properties based on Stephen King's fiction. Its placement is due largely to the fact that it draws almost nothing from King's short story, which concerns a suburban homeowner who discovers that his new lawn mowing service is fueled by supernatural powers. The film version, directed by Brett Leonard, focuses on virtual reality experiments conducted by scientist Pierce Bronson, which imbue mentally challenged handyman Jeff Fahey with godlike powers. Aside from the title, the only link to King's story is the name "Harold Parkette," who is the protagonist in King's story and an abusive dad in Leonard's film, both of whom fall victim to a homicidal lawnmower.

New Line Cinema prominently featured the author's name in the film, which was billed as "Stephen King's The Lawnmower Man." King took the studio to court and won a $2.5 million settlement. However, New Line continued to use King's name for the video release of the film, which led to contempt of court charges and penalties of $10,000 per day until his name was removed from all promotional material, as well as the forfeit of profits earned on the title during that time frame. Astonishingly, New Line released a sequel – minus any link to King — the following year.

Artemis Fowl

When Kenneth Branagh's feature version of Eoin Colfer's YA fantasy novel "Artemis Fowl" finally arrived on screen in 2020, fans of Colfer's novels decried the script's wealth of changes, additions, and deletions from the source material. These alterations often deviated in major ways from the books; the most notable of these is the depiction of Artemis, who is unquestionably a villain in the book but played with greater sympathy in the film version. "Fowl" also adds Artemis's father (Colin Farrell), who actually doesn't arrive until the second book, and removes his mother (Miranda Raison in deleted scenes), who gave Colfer's Artemis a degree of emotional resonance.

Characters are depicted in markedly different ways — Dame Judi Dench plays the male Commander Root in the film — but the most significant difference between the film and the book is the appearance of the Aculos, a device that allows the user to teleport any distance. Its addition is part and parcel of the movie's kinder, gentler Artemis Fowl; Colfer's Artemis has no problem kidnapping elf officer Holly Short and ransoming her for fairy gold. The movie Artemis needs a reason to commit such an act, and so added the Aculos as a bargaining chip for him to exchange for his father.

Adaptation.

Noting that Spike Jonze's "Adaptation." has very little connection to its source material — Susan Orlean's non-fiction book "The Orchid Thief," about an obsessive horticulturist — is in a certain sense missing the point of the film. Charlie Kaufman's Oscar-nominated script is in part about the challenges faced by screenwriters when tasked to turn a book into a screenplay, something that Kaufman himself experienced when he was hired by Jonathan Demme's production company to adapt "The Orchid Thief." Unable to deliver a straightforward adaptation, he instead wrote a fictionalized account of his own experience that wove Orlean's book into its comic fabric.

Neither the real nor fictional Kaufman (Nicolas Cage) appear in "The Orchid Thief" (the same goes for Kaufman's made-up brother Donald, also played by Cage), and his version of Orlean — a drug-using ego monster who is sexually involved with John Laroche, the subject of her book — is completely fictional. The film also shows Laroche (Chris Cooper) being killed by an alligator, which did not happen. And the hallucinogenic qualities of the ghost orchid, to which the film's Orlean and Laroche become addicted, are somewhat exaggerated and inconclusive, according to various horticultural sources.

The Golden Compass

When New Line Cinema released a film version of "The Golden Compass" in 2007, observers and fans hoped that it would echo the company's success in bringing "The Lord of the Rings" to screen. Despite a colossal budget of $180 million and a cast led by Nicole Kidman and Daniel Craig, the film was plagued by negative reviews, including those from fans of author Philip Pullman's novel of the same name, which kicked off his acclaimed "His Dark Materials" trilogy. At the center of many complaints were numerous liberties taken with the book by the film.

Chief among the cited problems was the script by Chris Weitz, which attempted to cram Pullman's epic novel into a 113-minute framework. This necessitated compressing a number of elements — as evidenced by the opening, which detailed much of the back story through wordy narration — and diluting characters that were beloved by readers. New Line also opted for a very different ending that took a completely different tack than Pullman's novel, closing on both an upbeat note and a cliffhanger to set up a trilogy which never happened. The script also blunted Pullman's decidedly anti-theological stance in order to stave off protests from religious groups. This decision further flew against fans' visions of the books, which helped to spell the film's demise at the box office — though a "His Dark Materials" series aired on HBO between 2019 and 2022.

World War Z

Given the production difficulties incurred by Marc Forster's 2013 film version of "World War Z," it's a minor miracle that the film was completed, much less a box office success. But for fans of its source material — the 2006 novel by Max Brooks — "World War Z" was a huge miss. It traded the gripping oral history structure of the original text for a straightforward action film anchored around star and co-producer Brad Pitt's U.N. investigator, as he attempts to stop the zombie problem while also keeping his family safe.

That singular focus is one of the primary differences between the film and Brooks' novel, which recalled the zombie outbreak from the perspective of multiple characters over a decade. Forster's film unfolds over the course of what appears to be a few weeks, which lends urgency to the material but also lessens the impact of the disaster, which ultimately seems easy to correct.

Other notable changes include the depiction of the zombies, which in Brooks' novel are slow-moving but implacable, like those seen in George A. Romero's zombie films; in "Z," they are fast and relentless, like the sprinting monsters in Zack Snyder's "Dawn of the Dead." They also adhere to a hive mind sensibility, while Brooks' zombies are a mindless horde. Perhaps the most significant change is the finale, which sees the creation of a vaccine that protects survivors: in Brooks' novel, victory is claimed through endless fighting, which turns the tide but at a great cost to humanity.

The Hobbit trilogy

Where to begin with the differences between J.R.R. Tolkien's novel "The Hobbit" and Peter Jackson's trilogy of feature films? Expanding the source material to three films required Jackson and co-scripters Fran Walsh and Philippa Boyens to balloon Tolkien's single-volume children's book into an epic multi-film adventure like the "Lord of the Rings" trilogy. And while much of Tolkien's "Hobbit" remains in Jackson's films, there are also a vast number of changes.

These include adding "Rings" characters Frodo (Elijah Wood), Legolas (Orlando Bloom), Galadriel (Cate Blanchett), and Saruman (Christopher Lee) into the story, all of whom are absent from the original text. There's also Evangeline Lilly's elf warrior Tauriel, who was intended to increase the number of female characters. Two of the film's key villains, the Necromancer (aka Sauron) and the orc Azog the Defiler, are only mentioned in Tolkien's book, but become full-fledged characters in the films.

A representative sampling of plot alterations includes Gandalf using a moth to call the eagles (they appear on their own in the novel) and Bilbo tricking the trolls (Gandalf does it in the book). The deaths of dwarf heroes Thorin, Fili, and Kili are consistent with the source material, but occur largely "off-camera" and are far more graphic than in Tolkien's text. And Sylvester McCoy's Radagast the Brown — a secondary hero in the films — doesn't rate more than a handful of mentions in any of Tolkien's writing.

Minority Report

Acclaimed science fiction author Philip K. Dick penned the short story on which Steven Spielberg's "Minority Report" is based; Dick's writing has served as the source material for such features and series as "Blade Runner," "Total Recall," and "The Man in the High Castle." Dick's fiction embraced a complex array of philosophical, technological, and metaphysical subjects — alternate realities, human identities, imaginary worlds — which often made their translation from page to screen a challenge for filmmakers. "Minority Report" required considerable reworking before its release in 2002.

Dick's story envisioned a future world where a select group of mutants with advanced mental abilities could predict that a crime would take place before it happened. When the head of the project learns that he has been predicted to commit a murder, his investigation yields a vast conspiracy. That basic premise turns up in Spielberg's film, but it streamlines and sanitizes many of the story's elements.

Among its changes: the project head, depicted by Dick as a middle-aged man in a failing marriage, is played by Tom Cruise as a younger man who works for the project (Max von Sydow plays its chief). The character's marriage is also on the rocks, but additionally saddled with a dead child and a drug problem. The "precogs," who are physically and mentally disabled by their mutation in the story, are otherwise untouched in the film and even allowed to return to their lives.

Dracula

Bram Stoker's 1897 novel "Dracula" has served as the inspiration for hundreds of feature films, television productions, radio and stage plays, music recordings, and other pop culture items. The novel's structure, which unfolds in the form of letters and diary entries, has proven difficult to translate for dramatic purposes. As a result, few "Dracula" adaptations follow the book, save perhaps for "Bram Stoker's Dracula" (which itself takes numerous liberties with the source material).

Universal Pictures' film version of "Dracula" has been one of the most popular and best-known adaptations since its release in 1931. But it draws on only a small portion of Stoker's novel: its main source of inspiration is actually a stage play written by actor Hamilton Deane in 1924 and revised in 1927 by writer John L. Balderston. The play significantly compresses the book, relegating all of the action to Dr. Seward's sanatorium and Dracula's property at Carfax Abbey in England. Numerous characters are excised, including Dracula's brides, and Jonathan Harker does not bring Dracula to England, as he does in the novel.

The most significant change is the depiction of Dracula himself, who is not only onstage for much of the play (he goes unseen for most of the book) but also transformed from an elderly man who grows younger to a courtly, even romantic figure. That take on the Count, and not Stoker's, is one that's most frequently associated with the character.