Everything Oppenheimer Gets Right (And Wrong) About The True Story

Contains spoilers for "Oppenheimer"

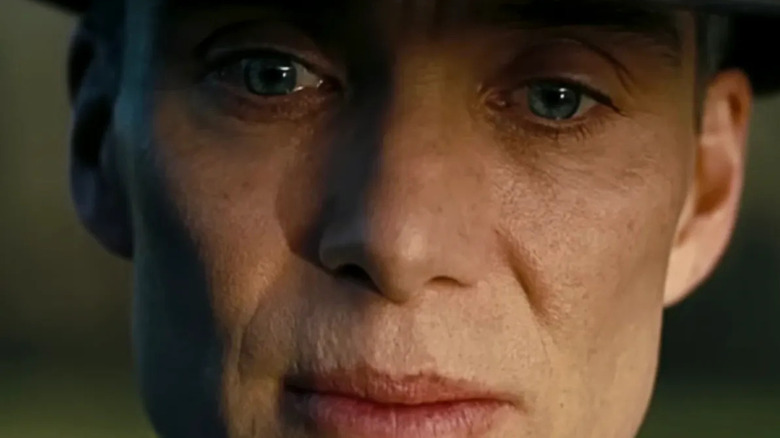

Christopher Nolan's "Oppenheimer" has finally arrived. The biopic about the theoretical physicist who ran the Manhattan Project is one of the most hotly anticipated and highly rated movies of the year. It's also one of the most historically accurate films ever made. That's largely because Nolan is so meticulously faithful to the source material ... something fans will notice down, to the title character's preference for ice-cold martinis and pork pie hats. "Tenet" star Robert Pattinson gifted a copy of the book in question — 2005's Pulitzer Prize-winning "American Prometheus" — to Nolan in early 2021. The resulting film came together incredibly quickly, though the book it's based on took two authors more than 25 years to complete, compiling 50,000 pages of once-secret documents and interviews with just about everyone J. Robert Oppenheimer ever knew.

Anyone familiar with Nolan's filmography should recognize why he was so attracted to the subject matter. Though "Oppenheimer" is less gimmicky and more introspective than any of his previous 10 films, the story contains several Christopher Nolan hallmarks. It's a somber period piece from a not-too-distant past about a great man in well-tailored suits with an interest in science, problems with women, and a troubled mind. For the most part, "Oppenheimer" presents the physicist much as he was, to the best of anyone's knowledge. In fact, rather than making mistakes or inserting historical inaccuracies, the three-hour film instead has to gloss over or omit some fascinating details. This is how close Nolan and company got to the truth.

His background

Upon meeting Lewis Strauss, Oppenheimer (Cillian Murphy) remarks that he can relate to the fact that Strauss is a self-made man because his father was, too. In that same conversation, during which Strauss is trying to convince Oppenheimer to sign on as director of the Institute of Advanced Study in Princeton, the two briefly commiserate about anti-Semitism. Because Murphy plays Oppenheimer throughout the film's entire runtime, Nolan starts with the physicist's college days and doesn't delve too deeply into his childhood or socioeconomic and religious background.

Robert's father, Julius, was a German Jew who fled to New York City in 1888. He really did start with nothing, turning a job at a textile factory into a business empire lucrative enough that the Oppenheimers eventually owned Picassos and Van Goghs. The family wasn't religious, and sent their children to a progressive institution called the Ethical Culture School. In the film, Oppenheimer claims the J. in his name didn't stand for anything. The book explains that it wasn't common practice for Jewish fathers to name their sons after themselves, but Julius added his name to Robert's birth certificate at the last second. Oppenheimer's privileged upbringing distinguished him from men like Strauss socially, though he was indifferent to both money and his Jewish heritage at various points in his life.

Oppenheimer was an odd child who was bullied by peers. He skipped grades, had obsessions with rocks and minerals, and was once violently hazed at summer camp. By his teenage years, he was already showing signs of both genius and instability.

The poisoned apple

While at Cambridge, Oppenheimer poisons his professor's apple after he's made to miss the beginning of a Niels Bohr lecture to clean up his sloppy lab work. In real life, Oppenheimer was notoriously clumsy with his experiments and his calculations, which was why he ended up working in theoretical physics. And that apple wasn't one of Nolan's creative flourishes. Oppenheimer did inject Patrick Blackett's apple with chemicals, which caused more of a scandal than what we see depicted in the movie.

In "Oppenheimer," the aggrieved student wakes up in a panic the following morning and rushes back to the classroom to find his idol, Niels Bohr (Kenneth Branagh), about to take a bite. To remedy the situation, he simply says he's spotted a wormhole (a bit of an inside joke for physicists) and tosses it in the trash. The real Oppenheimer was struggling with more serious mental health issues.

The lacing of the apple, possibly with cyanide, did actually occur, and the University found out about Oppenheimer's misguided revenge plot. Blackett never ate the apple, and whether the substances would've killed him or merely made him sick is unknown. Conflicting accounts and his father's influence kept young Oppenheimer from getting arrested or expelled. The ordeal was seen as a cry for help, and he made an arrangement with the school to attend regular sessions with a psychiatrist to address these issues.

His politics

Audiences expecting to see a movie about World War II may have been surprised by how much "Oppenheimer" is instead about closed-door politics. One framing device Nolan uses to tell the story is the same one that authors Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin employ in the book: The hearing during which Oppenheimer's security clearance and loyalty to America were called into question. As in "American Prometheus," the film ultimately remains ambiguous about whether or not Oppenheimer was ever officially a member of the Communist Party, though both seem to put more stock in the idea that he was most likely a leftist FDR supporter who had associations with card-carrying communists.

In "American Prometheus," Bird and Sherwin quote Oppenheimer as claiming he was so apolitical and disinterested that he didn't know the stock market had crashed in 1929 until Ernest Lawrence (Josh Hartnett) told him six months later, and didn't vote until 1936. His support of left-wing causes — particularly of antifascists fighting Franco during the Spanish Civil War, Jewish scientists escaping the Nazis, and the support of union workers in California — began around 1934 and continued until roughly the time he became involved in war efforts. Oppenheimer insisted he never joined the CP, but admitted in writing during background checks that he'd been, "a member of just about every Communist Front organization on the West Coast."

Additionally, his brother, sister-in-law, girlfriend, wife, best friend, and several of his students and eventual employees were, at points in their lives, active communists. But whether radical ideas or associations with political parties are incompatible with patriotism is one of the larger questions Oppenheimer was forced to contend with.

Jean Tatlock

Nolan's Oppenheimer says that only a fool or a child would presume to know what goes on in a relationship. He's talking about his wife, Kitty, but the sentiment is even more applicable to his romance with Jean Tatlock (Florence Pugh). Brilliant in her own right, she was studying to become a child psychologist when she and Oppenheimer met at a party, where they bonded over their inner demons as much as their left-leaning ideologies.

The film touches on Tatlock and Oppenheimer's intense but relatively short-lived relationship, and their final tryst, after which she died by suicide. The truth is much more complicated and salacious. Tatlock was annoyed at Oppenheimer's habit of bestowing gifts upon his friends and lovers. But in real life, she rebuffed his bouquets and his marriage proposals ... and regretted it. Tatlock was also rumored to have carried on a long-term affair with her friend Mary Ellen Washburn. "American Prometheus" proposes that her repressed sexual identity contributed to her psychological distress.

But the most outrageous allegation from the book that doesn't appear in the movie is that Tatlock's suicide may not have been a suicide at all. When her father discovered her body, he burned her letters before calling the police. Since her affair with Oppenheimer was relatively common knowledge, it's been hypothesized that a government official may have had her killed out of fear that Oppenheimer shared state secrets she could pass on to the Russians.

His marriage

Kitty Oppenheimer's incredible backstory is exposition-dumped in one brief and underwhelming monologue. "Oppenheimer" depicts Kitty (Emily Blunt) as an unhappy mother and jealous wife with a moderate drinking problem, but the real Kitty was a more extreme version of the one we see on screen. The only child of an upper-class German family, Kitty claimed she was a princess (she wasn't). She frequently enrolled in colleges but failed to take any classes. She divorced her first husband, Frank Ramseyer, after learning he was gay and addicted to drugs. Her second husband, the Communist Joe Dallet, died in battle in Spain, and Kitty indeed became pregnant with Oppenheimer's baby while married to Richard Harrison.

Dating married women (and cheating on his wife) wasn't unusual for Oppenheimer, who was even more of a womanizer in real life. Letters prove a long-term relationship existed between Oppenheimer and his friend Richard Tolman's wife, Ruth. "American Prometheus" reveals just how unhappy and unwell Kitty was. She was resentful of her husband's lovers and his fame. An alcoholic who got into several car crashes and sustained broken bones from falls, Kitty took to bringing her own bottles with her, favored liquor over food at parties, and frequently fell asleep with lit cigarettes. Kitty may have suffered from untreated postpartum depression, resulting in an emotional disconnect between her and her children.

The Manhattan Project

The most accurate part of "Oppenheimer" is the stretch that takes place at Los Alamos. Nolan manages to pack hundreds of pages of science and bureaucracy into a gripping hour of film. During these years — 1942 to 1945 — we see Leslie Groves (Matt Damon) recruit Oppenheimer to head up the secret weapons lab. The real Groves and Oppenheimer had political and operational disagreements, but they respected each other and worked well together. Groves wanted the scientists to become soldiers and wear uniforms (although Oppenheimer, always sickly, failed his physical), and he did insist upon compartmentalization, but conceded that his physicists could meet once a week to share ideas for the sake of progress. Oppenheimer's friend Isidor Rabi (David Krumholtz) refused to work on the Manhattan Project officially but did consult from time to time, and Edward Teller (Benny Safdie) did favor the hydrogen bomb. The German refugee from Britain, Fuchs, was indeed a Soviet spy.

The technical specs are, more or less, correct, too. A cyclotron was used to accelerate particles. For a brief time, the theorists did fear they'd ignite the atmosphere. The uranium and plutonium cores were about as big as represented by the fish bowls. The bomb was referred to as "the gadget" as a security measure. And the crew was relieved to learn from Niels Bohr that the Germans took an engineering wrong turn, despite the head start that Werner Heisenberg had given them. The weather was in fact a problem on the planned date of the Trinity test, just as it is in the movie. The film doesn't, however, include the fact that the U.S. considered having Heisenberg assassinated and poisoning German food supplies.

The Chevalier incident

A casual conversation that took place in a kitchen between friends derails Oppenheimer's life, both in reality and in Nolan's movie. Haakon Chevalier (Jefferson Hall) and his wife are over for dinner when Chevalier approaches the physicist to say that the academic community has been complaining that the Americans aren't sharing intelligence with their allies. That includes Soviet Russia. He mentions that an acquaintance, another physicist named George Eltenton, made it known he could channel such information, should anyone want to divulge their secrets. Oppenheimer says that would be treason, and Chevalier changes the subject.

Oppenheimer did report Eltenton, but not until some time after Chevalier's visit, and he did concoct a fake story (it involved three unnamed, non-existent intermediaries at Berkeley) to protect his friend. He admitted the truth (which included the fact that his brother, Frank, had also been targeted by Eltenton) to Groves eventually. However, the "cock and bull story" came back to haunt him and undermined his character during his security clearance hearings. In the end, Chevalier's name came out anyway, as did Frank's, and both were blacklisted. Chevalier moved to France to work as a translator. For his part, he maintained that he was simply alerting Oppenheimer to Eltenton's scheme and not soliciting nuclear intel.

The decision to drop the bomb

As the movie hurtles toward its climax, Oppenheimer and Lawrence are invited to a Department of Defense meeting to discuss whether to drop the atomic bombs, and if so, on which Japanese cities. Prior to this meeting, some of the scientists working at Los Alamos had begun to discuss the ethics of the gadget. Oppenheimer had assured them that public awareness of the weapon could be terrifying enough to end all wars. Behind closed doors, some wonder aloud if a demonstration might be enough, or if civilians should be warned in advance. The military shoots down those ideas as it would jeopardize the mission and the safety of the pilots. It would also be a national embarrassment if the bomb turned out to be a dud. The group chooses two targets out of 11 (Groves says the first will show off the bomb and the second will prove they can keep up an assault); Kyoto is withdrawn from consideration because of its cultural significance — and the fact that Secretary of War Henry Stimson honeymooned there.

That's all true. Oppenheimer had much less power once the A-bomb was invented, and the scientific community had begun to question its necessity. Germany had already surrendered. Hitler had died by suicide in his bunker. Japan was, Stimson knew, likely to surrender in the coming months if the country was permitted to keep its Emperor. Unconditional surrender was preferable, however, and Hiroshima and Nagasaki were chosen as targets. Oppenheimer defended the decision throughout his life, though he did tell President Truman that he felt he had blood on his hands, as he does in Nolan's film.

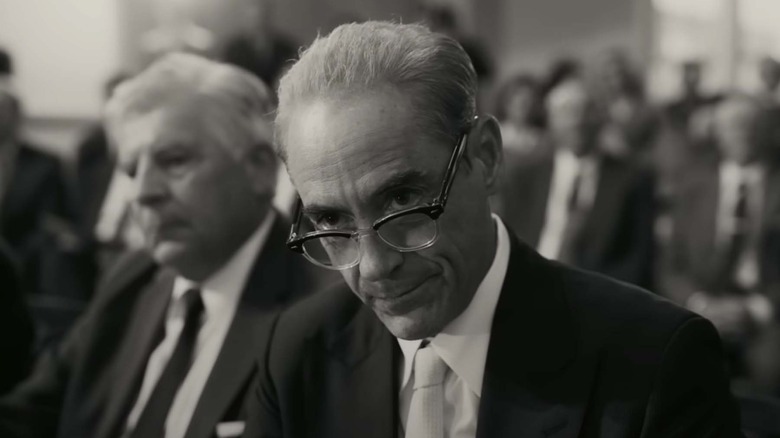

Rivalry with Strauss

Though Oppenheimer himself can be seen as an antihero of sorts, the real villain in "Oppenheimer" is Lewis Strauss (Robert Downey Jr.). Nolan uses an important moment in Strauss' life — the Senate confirmation hearings for his appointment as Secretary of Commerce — as one of the film's two framing devices (the other is Oppenheimer's sham security clearance hearing, which Strauss himself nefariously orchestrated). Strauss is depicted as a vindictive man who had it out for Oppenheimer after he was embarrassed by the physicist during a debate about the export of isotopes, among many other petty perceived slights.

In real life, there was even more animosity between these two figures from history. Like many competitive contemporaries (Mozart and Salieri, Hamilton and Burr) Oppenheimer and Strauss were as alike as they were different. Both were the sons of German Jewish immigrants and businessmen — though a recession hit Strauss' family harder. Both were smart and ambitious, and both planned to study physics, but Strauss couldn't afford to continue his education. Oppenheimer was liberal, Strauss was conservative. Oppenheimer was secular, Strauss was religious. The shoe salesman turned political insider did orchestrate the ruin of Oppenheimer's reputation, but — as in Oppenheimer's analogy of two fighting scorpions — he brought about his own ruin in the process. Three votes, including that of Senator John F. Kennedy, made the difference, and Strauss failed to secure the nomination.

Postwar life

"Oppenheimer" ends with a wholly invented scene involving Albert Einstein. Strauss had long believed that Oppenheimer turned Einstein against him. Alden Ehrenreich, as an unnamed aide, witheringly tells him that maybe they were discussing something more important. When we finally see that conversation play out, we learn that Einstein commiserated with Oppenheimer about the nature of scientific legacy, and Oppenheimer confides in him that he worries he did set off a figurative unstoppable chain reaction with the advent of nuclear power.

Einstein and Oppenheimer did know each other, and Oppenheimer did receive the medal we see put around his neck. It was the Enrico Fermi award for his contributions to physics, and it came with a $50,000 cash prize. The distinction was awarded to him by JFK, who died just days before the ceremony. Lyndon Baines Johnson bestowed the honor upon Oppenheimer in a move that was widely seen as an apology for his treatment during the McCarthy era.

The father of the atomic bomb continued to speak out about the threat of nuclear war, favoring policies of international cooperation and candor. But he was never the same after the humiliation he suffered when his loyalty was questioned and his clearance was revoked. The Oppenheimers lived part-time in the Virgin Islands away from the limelight, where he rediscovered his childhood love of sailing. A lifelong smoker, he died of throat cancer in 1967 at the age of 62.