The Ending Of Stay Explained

After the runaway success of "The Sixth Sense," the early 2000s saw a spate of thrillers with wild twist endings where nothing was quite as it seemed, from the Agatha Christie-style mindbender "Identity" to flicks like "Wicker Park" and "The Butterfly Effect," where soulful young men were haunted by lost loves. Charlie Kaufman's 2002 comedy "Adaptation." spoofed this mini-genre as it was happening, via one character's hack script about a killer, victim, and cop who are all somehow the same person. Meanwhile, Marc Forster's 2005 mystery "Stay" offered up two soulful young men for the price of one, and an entire world where everyone is the same person.

Forster and his longtime editor Matt Chesse employ a disorienting shooting style, using CGI and camera tricks to move seamlessly from one scene to another. An apartment door opens up into a zoo; characters appear, disappear, and switch places seemingly at random. Meanwhile, David Benioff's script piles on so many odd moments, portentous interactions, and thoughts on the intersection of dreams, death, and art that it's clear something is off-kilter, perhaps supernatural, from the start. In the end, the source of the film's strange happenings is not ghostly, but all too human: The need to make sense out of a senseless tragedy and the desire to be remembered after death. Let's take a look at the end of "Stay."

What you need to remember about the plot of Stay

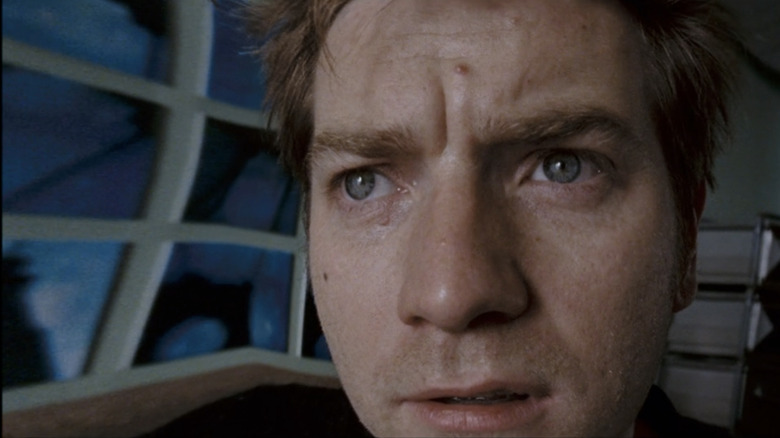

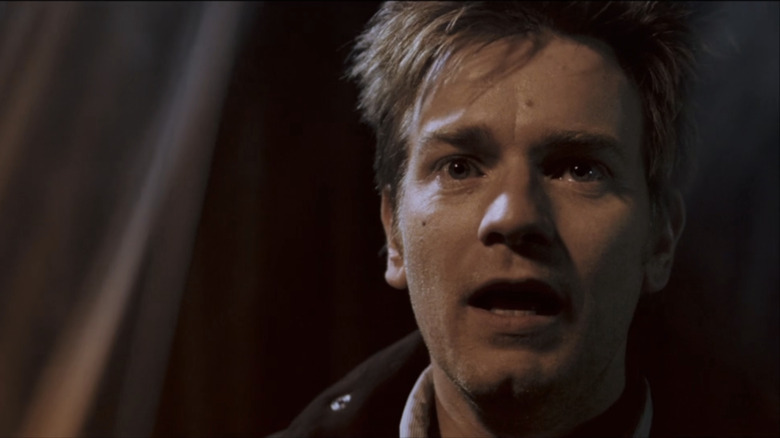

New York psychiatrist Sam Foster (Ewan McGregor) takes on the clients of a beleaguered colleague (Janeane Garofalo in a small but vital role). One of them is Henry (Ryan Gosling), a 20-year-old art student who set his car on fire in the middle of the Brooklyn Bridge. Henry is having difficulty separating fantasy from reality, and during their second session together he announces to Sam that he plans to kill himself in three days, on his 21st birthday.

Determined to save his patient, Sam sets out to uncover the truth about Henry and his delusions. But the further he delves, the more murky and confusing things become. Sam visits Henry's childhood home and meets his mother (Kate Burton) and the family dog, only to be told that both mother and dog died years earlier. He tracks down a young woman (Elizabeth Reaser) who Henry was in love with, but she has no recollection of him. Meanwhile, Sam's live-in girlfriend Lila (Naomi Watts), a self-destructive artist, slips up and calls him "Henry."

Before long, Sam is having problems telling fantasy from reality, as he sees the same things play out on different days and conversations start all over again — and that's before Henry seems to miraculously cure Sam's mentor (Bob Hoskins) of blindness with the touch of his hand. Sam finds his patient exactly where he said he would be, at the top of the Brooklyn Bridge at midnight on his 21st birthday, gun in hand.

What happened at the end of Stay?

"Stay" begins with the scene of a horrible wreck on the Brooklyn Bridge, seen from under a car that suffers a tire blowout and flips over in the middle of traffic. We return to that crash several times, each time learning a little bit more: Henry is driving the car, his parents (Burton and Hoskins) are in the backseat, and his girlfriend (Reaser) is up front. But we don't know exactly what is happening or when it happened until the final scene, as Henry, true to his word, shoots himself on the bridge in front of Sam.

The fatal moment fades into light, but when the camera comes back into focus we are not in the aftermath of Henry's suicide, but of the crash that began the film, as Henry — the lone survivor — lies injured on the street and a man and a woman who look exactly like Sam and Lila tend to him. Soon, we recognize the rest of the bystanders on the bridge as people Sam and/or Henry saw or interacted with. The entire story we've been watching appears to be Henry's hallucination as he hovers near death.

After an ambulance finally arrives and takes Henry away, the man we knew as Sam, shaken from the accident, asks the woman we knew as Lila to have a cup of coffee with him. She accepts, and in that moment we see brief flashes of the alternate reality love affair they shared, suggesting perhaps that Henry's world was more than just a dying man's dream.

An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge

"Stay" did not invent the convention of a story existing in the mind of a doomed or dying character, of course. It is a well-worn trope, seen in films like Terry Gilliam's "Brazil," Adrian Lyne's "Jacob's Ladder," and the original ending of Neil Marshall's "The Descent." The most famous example of this device is arguably one of the earliest: The Civil War-set 1890 short story "An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge" by Ambrose Bierce. In it, a Confederate sympathizer escapes being hanged by the Union army and comes home to his wife and family, but the perilous journey turns out to be nothing but a dream in the instant before his execution.

Bierce's story pulls the rug out from under the reader, getting within reach of a happy ending before snapping back to cold, cruel reality. "The Descent" and "Brazil" work in this vein as well, teasing the possibility of escape and then yanking it away. "Stay," however, uses this device in a different way. Henry's dream-world escape isn't for himself, but for his loved ones who died in the crash, his parents and girlfriend, who now live in his fantasy while he sacrifices himself. If he lives, it is through his art and the impact he had on the people around him, including Sam and Lila.

Doubles and doubles of doubles

As real-world Henry lies dying on the ground, he (and we) see the crowd of bystanders who populated his fantasy. Sam, trying to help but unable to save him, becomes a dream-world psychiatrist trapped in a similar situation. Lila, a beautiful stranger, represents the loving future he had wanted with his girlfriend. Garofalo's Beth, a panicked witness, is similarly frozen by fear and grief in Henry's fantasy. Others appear in the crowd and become a kind of repertory company in Henry's fantasy: BD Wong as a colleague of Sam's, Jessica Hecht as a mother whose son's balloon keeps floating away, Becky Ann Baker as a paramedic in one world and a fry cook in the next.

Even within the dream, several people appear in multiple roles, and Marc Forster fills the background of some scenes with twins and triplets, doubles upon doubles. The reappearance of actors in multiple fantasy roles is meant to be subtle, the kind of thing viewers only catch on repeat viewings, but in the last two decades some of the actors meant to blend into the background have become stars in their own right. The late Mark Margolis appears here as a subway rider and then again as a bookstore manager; a character actor for decades, he became best known in the years after "Stay" for his work on "Breaking Bad" and "Better Call Saul." And future Emmy-winner Sterling K. Brown is unmissable, first as a finance bro and then as a college actor working with Athena (Reaser).

To be or not to be

The scene that Athena and her partner are working on is from William Shakespeare's "Hamlet," specifically the Act 2 conversation between Hamlet and his friends Rosencrantz and Guildenstern. The film's selection of this scene is very much intentional, as Sam enters the rehearsal room just as Athena recites the famous line "O God, I could be bounded in a nutshell and count myself a king of infinite space, were it not that I have bad dreams."

It's a pointed reference, especially in hindsight; Henry's fantasy encompasses the entire world and the lives of everyone we see, but ultimately only exists in his dying, haunted mind. There are a number of "Hamlet" references throughout the film: The bystanders who become players in Henry's dream world resemble the company of actors Hamlet utilizes to "catch the conscience of the king" with their play-within-a-play. Henry's last name, Letham, is an anagram of Hamlet, and like Shakespeare's melancholy Dane, he is a mopey dreamboat poised between action and inaction, life and death.

Hamlet's "To be or not to be" monologue is perhaps the most famous consideration of suicide in the English language, as he waffles (to pretends to, depending on your interpretation) between duty to his dead father and the desire to end it all. The film makes that predicament literal, placing Henry and his infinite kingdom in a liminal space where he could live or die by the next moment.

Does Henry die?

Does Henry succumb to his injuries? The fantasy world he conjures seems driven by survivor's guilt, that he should live while those he loves all die; when Sam visits Henry's apartment, the words "forgive me" are scrawled in tiny letters across every wall. In "An Occurrence on Owl Creek Bridge" and other versions of this trope, the main character's dream is usually depicted as their mind's final act before being permanently snuffed out. It makes sense both realistically and thematically that Henry's vision, in which his loved ones are better off for never knowing him, is the last hopeful act of a dying man.

But the film doesn't play as straightforward as that. For one thing, as Henry is loaded into the ambulance, he appears to be in a body bag that hasn't been zipped up all the way. His head is still visible, implying that he is still alive, if barely, as he departs the film. A moment later, when Sam asks Lila out for coffee, we see flashes of their fantasy life together. This could be a flash-forward to a real-life romance for the two of them, but it could also indicate that not only is Henry still alive, but that the "real world" we're watching is in fact another layer of fantasy.

Worlds within dreams

Not surprisingly, dreams and their interpretation are a recurrent theme in the film. The invocation of "Hamlet" leans heavily on dreams in the literal sense, but also in the sense of aspiration: Athena recites Hamlet's dialogue even though she is playing Ophelia and dreams of a better role. Earlier in the film, Sam's mentor Leon (Hoskins) invokes Freud's "dream of the burning child," in which a man receives a vision of his recently dead son, telling him that he is on fire. When the man awakens, he sees that a candle has fallen on his son's body. The story has had many interpretations over the years; some see it as wish fulfillment, while others read it as an expression of guilt.

Both interpretations get a heavy workout in Henry's fantasy world, which allows him to work through his guilt of being responsible for the crash. The dream of the burning child also points to the way that one's physical surroundings and experience can inform dreams, just as the witnesses to the crash become characters within Henry's world. At one point Lila — who, with her artistic ambitions and suicidal impulses, is a doppelganger for Henry — wonders aloud if anyone will ever remember her and her artwork after she dies. By the end, Henry has not just created a world in his dreams, but has ensured that he will be remembered, if only by those people present on the bridge.

What has the director said about the ending?

In a 2006 interview with Time Out London, director Marc Forster admitted that he had a different interpretation of the ending than writer David Benioff did. "What bothered me in the script was that it was sort of 'Twilight Zone' at the end," he said, comparing the climax to the kind of twists that often ended episodes of Rod Serling's classic anthology series. "I felt the ending shouldn't be the point of the movie. The point of the movie is the journey ... and not just the big reveal moment. So you have more of an open ending and different interpretations if you like."

That interview also answered a question that may have been bugging viewers through the entire film: Why on earth are Ewan McGregor's pants so short? While you might have chalked it up to Sam's general mid-2000s indie aesthetic, it turns out that Forster had a thematic reason for the character's high-waters. "When he kneels next to Ryan [Gosling's character] on the street at the end," Forster explained, "from Ryan's perspective, when he looks at him, his pants are up. So from his perspective he sees short pants."

This possible tongue-in-cheek explanation answers one question but raises more: If Sam's short pants made such an impression on Henry's dream world, why not anyone else's sartorial choices? Wouldn't the people whose shoes he couldn't see be rendered shoeless, or even footless, in his fantasy? Perhaps that requires dreams to make too much sense.

Critical response was not positive

Despite "Monster's Ball" and "Finding Neverland" director Marc Forster at the helm and the collected star power of Ewan McGregor, Naomi Watts, and Ryan Gosling, "Stay" was a box office bomb in October 2005, failing to crack the top 10 at the box office in its first week of release and all but disappearing from theaters after its second week. Critical reception was even worse, with many critics taking issue with a five-minute ending that essentially invalidates the 90 minutes that came before it. The Village Voice's Rachel Aviv also called out the film's somewhat ridiculous take on therapy and mental illness, where Henry's suicidal ideation is treated as "a 'mind-bending' flourish of special effects."

But the film had some notable champions. Roger Ebert's three-and-a-half star review praised Forster's way of using the camera to depict his characters' decaying reality, with Ebert writing, "The visuals are crucial to the movie's point of view, and ultimately to its meaning." Likewise, Peter Travers for Rolling Stone found it "arty and provocative" (as opposed to "arty and pretentious") and reserved special praise for Watts, who turns in the film's best performance despite being on the margins of the story. Travers and Ebert's positive takes were ultimately outliers, as critical opinion of the film solidified into labeling it an overly stylish misfire.

After the dream

Nearly two decades later, "Stay" is little more than a footnote in the careers of its cast and crew. No one's career was ruined by this dud, and in fact everyone involved has gone on to bigger and better successes. Marc Forster followed up the film with "Stranger Than Fiction," "The Kite Runner," and the 2008 James Bond sequel "Quantum of Solace." In recent years he has settled into a thoughtful journeyman career, directing respectable mid-budget movies like 2022's "A Man Called Otto," starring Tom Hanks. David Benioff scripted Forster's "The Kite Runner" adaptation in 2007 and worked on the script for 2009's "X-Men Origins: Wolverine" before becoming famous — and then infamous — as the co-creator (alongside D.B. Weiss) of "Game of Thrones."

McGregor had finished playing Obi-Wan Kenobi (or so he thought) in the "Star Wars" prequels just a few months before "Stay," and has cultivated an eclectic acting career, playing everything from Jesus in "Last Days in the Desert" to the title role in Forster's 2018 Disney film "Christopher Robin." Watts ended 2005 in the arms of King Kong, and in 2017 she reunited with her "Mulholland Drive" director David Lynch for a much more critically acclaimed exploration of dreams and reality, "Twin Peaks: The Return." Gosling, meanwhile, spent years playing stone-faced hunks and white saviors of jazz before getting silly in 2016's underrated "The Nice Guys" and as Ken in the 2023 megahit "Barbie."

If you or someone you know is struggling or in crisis, help is available. Call or text 988 or chat 988lifeline.org