Underrated '70s Movies You Need To Watch

The 1970s are often referred to as Hollywood's second golden age, a period of filmmaking since mythologized by an endless stream of books, essays, and documentaries (most notably, perhaps, Peter Biskind's bestseller "Easy Riders, Raging Bulls"). As the studio system collapsed under its own excess and ticket sales for ossified mega-productions plummeted, executives turned to young filmmakers in the hopes of figuring out what audiences wanted to see. For a brief period, those directors — with last names like Spielberg, Scorsese, Coppola, Ashby and Altman — were in perfect harmony with audience tastes.

Ask any person to name their favorite films from the period, and you'll often hear the same answers: "The Godfather," "Jaws," "Stars Wars," "The Exorcist," "Chinatown," "Network," "Taxi Driver," "Nashville." The period was so rich, however, that such a list doesn't even begin to scratch the surface. The decade was so artistically rich and vital that it produced a number of titles that were seen as failures at the time, but have now been rediscovered as classics.

It would be impossible to make a definitive list of must-see films from the 1970s; it would be equally foolish to try and narrow down the overlooked titles that deserve recognition. But if you're searching for a good place to start, here are 15 underrated '70s films just waiting to become your next favorite film.

Brewster McCloud (1970)

Perhaps no director personified the iconoclastic, rabble-rousing attitude of the 1970s better than Robert Altman, who kicked off the decade with "M*A*S*H" and followed it up with "McCabe & Mrs. Miller," "The Long Goodbye," "Nashville," and "3 Women." The prolific filmmaker churned out a hefty number of classics (both major and minor) during that time (he directed 13 films between 1970-1979), including this surrealistic comedy that was released the same year as "M*A*S*H" and was largely overshadowed by the latter's success.

Bud Cort stars as Brewster McCloud, an eccentric loner living in the Houston Astrodome who dreams of taking flight — not with an airplane, but with large bird wings he's been constructing in his secret apartment high above the baseball field (in real life, the Eighth Wonder of the World did have private accommodations). His trench coat-clad (sometimes with nothing underneath) guardian angel (Sally Kellerman) guides him on his quest, covering for him when his enemies start turning up dead, covered in bird crap. Michael Murphy costars as a "Bullitt"-skewering detective investigating the murders, while Shelley Duvall made her film debut as a quirky girl who catches young Brewster's eye and an off-the-wall Rene Auberjnois is a lecturer/narrator who seems to be ... turning into a bird?

Given the rousing reception greeted "M*A*S*H" earlier that year, critics at the time were a bit disappointed in the strange, circuitous "McCloud," which Vincent Canby of The New York Times called "dim, pretentious, and more than a little cruel." Even the more positive Roger Ebert, who found its freewheeling, absurdist narrative "more complex and difficult than 'M*A*S*H,'" conceded, "I'm not sure it's about anything." Yet critical assessment has only grown stronger as the film has attained cult status, making it essential viewing for any Altman fan — and if nothing else, it has one of the all-time great closing credits.

Watermelon Man (1970)

Before he helped launch the Blaxploitation genre with the independently-financed "Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss Song," Melvin Van Peebles made his only foray into studio filmmaking via "Watermelon Man." Hot off the heels of the French New Wave inspired romance "The Story of a Three Day Pass," Van Peebles got Columbia Pictures to produce his sophomore feature, a politically-charged reimagining of Franz Kafka's "The Metamorphosis."

Comedian Godfrey Cambridge begins the movie in whiteface, playing Jeff Gerber, a caucasian insurance salesman whose life is peachy keen until he awakens one morning as a Black man. Initially unsympathetic to the plight of Black Americans, Jeff's perspective quickly changes when he's suddenly victimized by the same discrimination he practiced in his daily life. Keep in mind, however, much of this is played for laughs — even if there is significant social satire beneath the surface.

In an essay penned for the film's Criterion release, Racquel J. Gates made the argument for why "Watermelon Man" shouldn't be viewed only as a warmup for "Sweet Sweetback," as it so often is. Working within the studio system, Van Peebles produced a film "that skewers society's and popular culture's infatuation with whiteness." In using whiteface to cast a Black actor as a white character — in defiance of the studio's initial idea of doing the opposite — Van Peebles "transforms whiteness into something bizarre and unnatural," reversing "the logic of whiteness as norm."

Ultimately, "Watermelon Man" is "an example of a Hollywood film that expresses a Black-oriented perspective in spite of the myriad factors actively working to suppress any manifestation of Black radical politics," one that is a testament to its director's "creative brilliance, ingenuity, and sheer force of will."

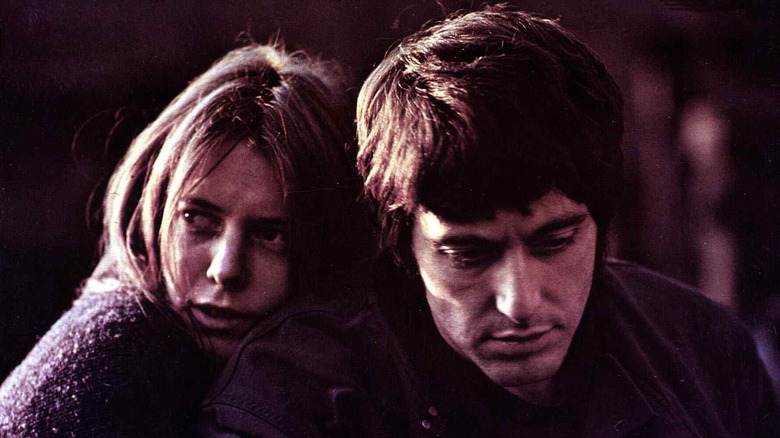

The Panic in Needle Park (1971)

Considering what a breakthrough "The Godfather" was for Al Pacino, it might surprise people to learn his first leading role was actually in this verite-style addiction drama. Directed by photographer-turned-filmmaker Jerry Schatzberg, it centers on Bobby (Pacino), a heroin addict who frequents the Manhattan junkie hangout known as "Needle Park." He falls in love with a homeless girl named Helen (Kitty Wynn) and quickly gets her hooked on drugs. As their addiction grows, their love story spirals into tragedy.

The 1970s gave rise to a new kind of movie star, one more closely resembling your neighborhood butcher than a matinee idol. Most of them cut their teeth on the New York stage, and what they lacked in conventional leading man good looks they made up for in acting talent (Gene Hackman, Elliott Gould, Dustin Hoffman). Pacino, who shot to stardom after "The Godfather," was an example of this. He was helped by a change in audience tastes: for a brief period, countercultural moviegoers were more interested in stories resembling their real lives instead of fantasy, which allowed a film like "Panic" to be produced at a major studio like 20th Century Fox as opposed to independently, like it would be today.

"The Panic in Needle Park" was greeted with widespread critical praise. Roger Ebert called it "a special and sometimes extraordinary movie." Rather than laud "the sensational elements" the studio emphasized in the ads, he zeroed in on the love story, which he found to be "a carefully observed portrait of two human beings."

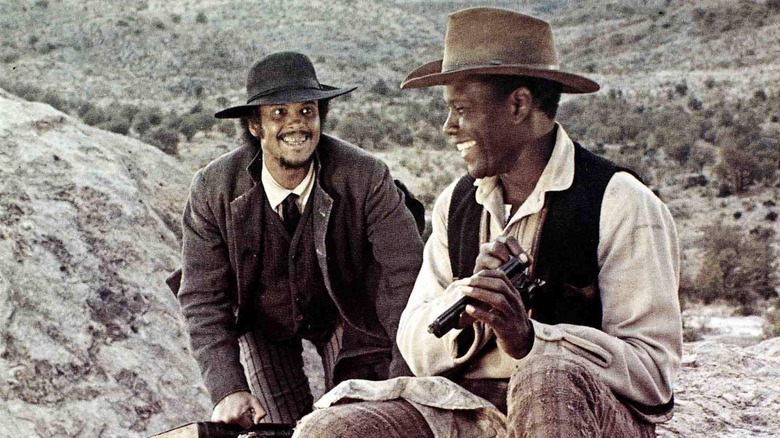

Buck and the Preacher (1972)

Black cinema reached new heights in the 1970s thanks to the rise of Blaxploitation, a subgenre of exploitation cinema centering on Black protagonists and Black power narratives. Not only did these films make stars of Pam Grier, Fred Williamson, Richard Roundtree, and others, but they also gave previously unthinkable opportunities to black filmmakers. Among them were Sidney Poitier, an Oscar-winning actor who made his directorial debut with this revisionist Western that adopts many blaxploitation touchstones within a studio production.

"Buck and the Preacher" centers on Buck (Poitier), a Civil War veteran now working as a trail guide for freed slaves looking to settle out West. Along the way he picks up a con artist named Preacher (Harry Belafonte), who tries to double cross Buck. But the two must join forces when a posse of white bounty hunters try to kidnap the passengers and return them to slavery.

The film represented a change of pace for Poitier, who in the years since his historic Oscar victory for "Lilies in the Field" had become typecast playing dignified, heroic individuals without any rough edges. With his directorial debut, Vincent Canby of The New York Times found he "showed a talent for easy, unguarded, rambunctious humor missing from his more stately movies." Robert Daniels of RogerEbert.com agrees, saying the film "allowed him to return to the lighter, comedic flair he displayed earlier in his career." Its critical assessment has only grown in the years since release.

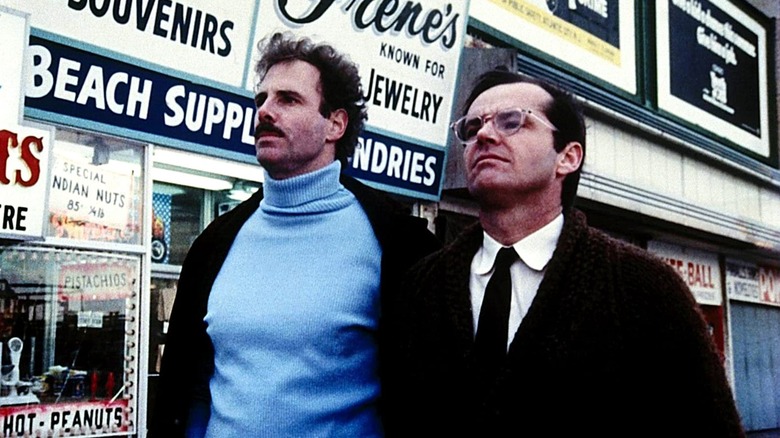

The King of Marvin Gardens (1972)

The New Hollywood of the 1970s came to fruition thanks in part to BBS Productions, a company run by novice producers Bert Schneider, Bob Rafelson, and Steve Blauner. After creating the TV music group The Monkees, they set their sights on Hollywood, understanding that younger audiences wanted movies by them and for them. They produced seven films between 1968-1972, including "Easy Rider," "Five Easy Pieces," and "The Last Picture Show," finally coming to an end with this polarizing character study.

"The King of Marvin Gardens" was Rafelson's directorial followup to "Five Easy Pieces," and re-teams him with BBS's favorite movie star, Jack Nicholson. He plays against type as David Staebler, a depressed late night radio host who reconnects with his estranged brother, manic conman Jason (Bruce Dern). Living in Atlantic City with his girlfriend, Sally (Ellen Burstyn), and her stepdaughter, Jessica (Julia Anne Robinson), Jason tries to rope his brother into a real estate scam, leading to tragic consequences.

Reviews at the time were decidedly mixed. Ebert called it "an original, individual, and often frustrating movie that takes a lot of chances and wins on about sixty percent of them." Roger Greenspun of The New York Times, on the other hand, panned it, saying that Rafelson's "kind of poetic realism," which came across well in "Five Easy Pieces," now felt like "the most pretentious of tired cliches." Yet this oddball odyssey has only grown in stature as an example of the defiant, unique films BBS churned out during its all-too-brief heyday.

The Friends of Eddie Coyle (1973)

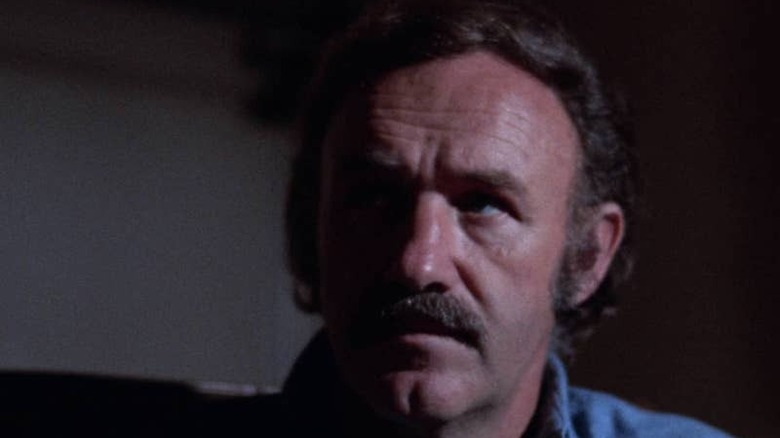

As the old Hollywood transitioned into the new, several stars who thrived during the studio system heyday suddenly found themselves adrift, forced to adapt or retreat to television (a main story point of Quentin Tarantino's "Once Upon a Time ... In Hollywood"). One actor who successfully made the transition was Robert Mitchum, who always felt more modern than his contemporaries. Mitchum worked steadily throughout the decade, making essentially the same kinds of noir thrillers he churned out in Hollywood's golden age, but now infused with contemporary sensibilities towards sex and violence. He gave one of his best performances in "The Friends of Eddie Coyle," playing an aging version of the tough guy he often portrayed.

Directed by Peter Yates, the flick stars Mitchum as Eddie Coyle, a low-level Boston gunrunner facing a second stint behind bars. He agrees to provide information to ATF agent Dave Foley (Richard Jordan) in exchange for his freedom, ratting out his closest criminal friends. But it doesn't take long for the mob to sniff out a rat.

In his four star review, Ebert said, "Mitchum has perhaps never been better" than as Eddie Coyle, a role that was "made for him: a weary middle-aged man, but tough and proud; a man who has been hurt too often in life not to respect pain; a man who will take chances to protect his own territory." The majority of critics praised the film as well, with Canby of The New York Times lauding Yates' evocation of "Boston's pool halls, parking lots, side-streets, house trailers, and barrooms."

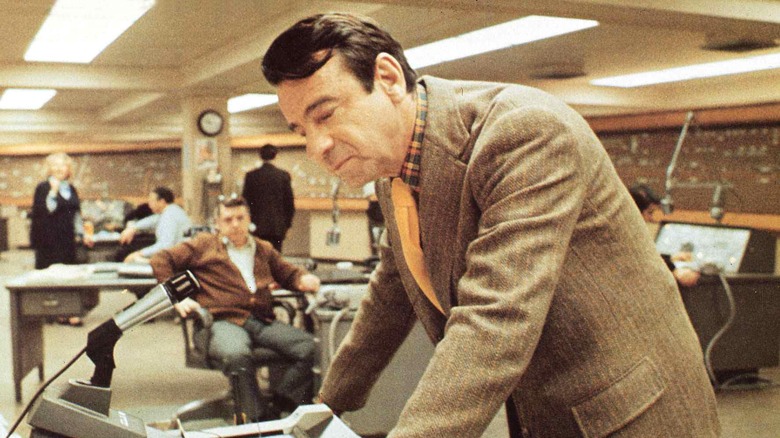

The Taking of Pelham One Two Three (1974)

An unofficial subgenre of '70s cinema is the New York City movie, in which the Big Apple becomes more than just a setting, but almost like another character. One of the best examples of this is Joseph Sargent's "The Taking of Pelham One Two Three," which holds up even better than the 2009 Denzel Washington/John Travolta remake, and whose villainous aliases might clue in "Reservoir Dogs" fans to a source of Tarantino's inspiration.

Walter Matthau stars as Zachary Garber, a world-weary transit policeman whose daily routine is interrupted by a subway car hijacking. The leader of the hijackers, "Mr. Blue" (Robert Shaw), threatens to shoot one hostage per minute if one million dollars in cash isn't delivered within an hour. Zachary must juggle negotiations with Mr. Blue, the bed-ridden NYC mayor (Lee Wallace), and the trigger-happy police to deliver the ransom before any hostages are killed.

One of the film's great qualities isn't just its feel for locations, but its casting of leathery-faced character actors in the leading roles (including Jerry Stiller as Zachary's fellow MTA officer and Martin Balsam, Hector Elizondo, and Earl Hindman as Mssrs. Green, Grey and Brown, respectively). As Ebert pointed out, the movie's appeal "doesn't depend on the plan or on the easily foreseeable plot," but "instead on a nice feel for New York City and some fine, detailed performances." He adds, "This sense of unforced realism extends even to the passengers being held hostage," which are "handled convincingly." It's a sentiment that was shared by the vast majority of critics, who praised its gritty naturalism and breezy suspense.

Hester Street (1975)

Although the '70s were a great period for young up-and-coming male filmmakers, the same wasn't true for women. Yet several female filmmakers, buoyed by the Women's Liberation Movement, found their way behind the camera, taking opportunities that had previously been denied to them under the studio system. Among those trailblazers was Joan Micklin Silver, who made her directorial debut with this Oscar-nominated period drama.

Set in 1896, "Hester Street" stars Carol Kane as Gitl, a Russian Jewish immigrant who arrives in New York with her son to reunite with her husband Jake (Steven Keats). While Jake has fully assimilated to life in America, Gitl struggles to adjust to her new home, leading to tensions in her marriage. (Silver emphasizes their culture clash by wisely choosing to have most of the films dialogue spoken in Yiddish with English subtitles.)

Although it takes place in the late 1800s, Gitl's story reflects the plight of women during the period, who were fighting against the structure of American society to assert their own independence. That was certainly true for Silver, who had to fight her way into the director's chair. During a 1979 interview at the American Film Institute, she recalled the "blatantly sexist things" thrown her way from studio executives, including one who said, "Feature films are very expensive to mount and distribute, and women directors are one more problem we don't need." Her tenacity paid off with sterling reviews, an Oscar nomination for Kane, and a Writers Guild Awards bid for her adapted screenplay.

Night Moves (1975)

The New Hollywood revolution of the 1970s began in the late '60s, when the studio system collapsed and younger filmmakers were handed the keys to the kingdom in the hopes of bringing in countercultural audiences. Among the films that kicked this into high gear was 1967's "Bonnie and Clyde," a violent gangster film that made stars of Warren Beatty, Faye Dunaway, and Gene Hackman. Hackman reunited with director Arthur Penn for "Night Moves," and it's a sign of how quickly things changed that their previous collaboration was a box office and Oscar success while their next was largely overlooked.

Hackman plays Los Angeles private eye Harold Moseby, immersed in a missing persons case to distract himself from the dissolution of his marriage. At the behest of aging B-movie star Arlene Iverson (Janet Ward), he travels down to the Florida Keys in search of her runaway daughter, Delly (Melanie Griffith, in her acting debut). Harry finds Delly living with her stepfather Tom (John Crawford) and his girlfriend Paula (Jennifer Warren), with whom he quickly begins an ill-fated affair.

Despite near unanimous praise, "Night Moves" fell prey to the great white circling the box office that summer: Steven Spielberg's "Jaws." In one fell swoop, "Jaws" fundamentally changed the kinds of films studios prioritized, as small scale character studies were scrapped in favor of blockbusters. Yet "Night Moves," which Roger Ebert declared was "one of the best psychological thrillers in a long time," has lived on as "a no-exit comment on the post-1968, post-Watergate times."

Mikey and Nicky (1976)

When she directed "A New Leaf" in 1971, Elaine May was only the third woman in history to be admitted to the Directors Guild of America, and the first since Ida Lupino to be given a deal at a Hollywood studio. May, who got her start as one half of the improvisational comedy duo Nichols and May (alongside fellow director Mike Nichols), blazed a trail for women not just in terms of landing a directing gig, but also in what kinds of movies they were expected to make. That's certainly true of her third film, "Mikey and Nicky."

John Cassavetes stars as Nicky, a petty hood who learns there's a hit out on him after he steals money from a local mobster. Holed up in a seedy hotel, he turns to his best friend, Mikey (Peter Falk), for help. The two spend the night evading a hitman (Ned Beatty) while hashing out the deep wounds from their lifelong friendship.

Shot on the streets of Philadelphia in a gritty, documentary style, "Mikey and Nicky" resembles the independently-financed films Cassavetes would shoot with his wife (Gena Rowlands) and friends (Falk, Ben Gazzara, Seymour Cassel). May shot hours of footage to capture that improvisational realism, leading to fights with the studio and a lengthy post production process that dragged on for years. When it finally hit theaters, it was unceremoniously dumped, and May didn't direct another film until 1987's "Ishtar" (itself an unfairly maligned flop). Thankfully, modern critical evaluation has been on its side.

Sorcerer (1977)

In the 1970s, the director was given free rein, as crumbling studios looked to fresh talent for insight into what audiences wanted. That came to an end when their modestly produced films began to balloon in budget, leading to some high profile flops. One of the most famous examples of this was "Sorcerer," a gloomy remake of "The Wages of Fear" that had the misfortune of opening the same summer as "Star Wars."

Hot off his Oscar-winning hits "The French Connection" and "The Exorcist," director William Friedkin exercised absolute control in telling this story of four men transporting gallons of nitroglycerin across treacherous terrain in the South American jungle. Shooting took place primarily on location in the Dominican Republic, which presented several production problems that caused the budget to skyrocket to a then-staggering $22 million. Its financial failure, alongside Francis Ford Coppola's "One from the Heart," Martin Scorsese's "New York, New York," and particularly Michael Cimino's "Heaven's Gate," hastened the demise of the New Hollywood. The massive success of "Star Wars" also marked a decisive shift in the sort of films studios would greenlight from then on out.

Yet, Sorcerer" has enjoyed a critical reevaluation in recent years, with director Quentin Tarantino naming it one of the ten greatest films of all time in a recent Sight & Sound poll. On the occasion of a 2014 restoration, Friedkin declared it was "the best film I've made," a sentiment shared by a growing number of viewers.

Blue Collar (1978)

The New Hollywood was a breeding ground for directorial talent, and some of its best filmmakers — including Martin Scorsese, Steven Spielberg, and Paul Schrader — are still working today. Schrader started out as a film critic before moving into screenwriting, quickly churning out a string of hits that included Scorsese's "Taxi Driver." He moved into directing with this gritty workplace drama that holds even greater relevance today.

"Blue Collar" centers on three Detroit autoworkers: Zeke Brown (Richard Pryor), Jerry Bartowski (Harvey Keitel), and Smokey James (Yaphet Kotto). Fed up with poor pay and even poorer workplace treatment, they decide to rob their local union office, only to discover a ledger linking the union to fraud and organized crime. Rather than turn it in to the police, they decide to blackmail the union for its return, leading to unexpectedly tragic consequences.

In his four star review, Roger Ebert called "Blue Collar" "an angry, radical movie about the vise that traps workers between big industry and big labor. It's also an enormously entertaining movie" and "an extraordinary directing debut for Paul Schrader." It's a sentiment shared by the vast majority of critics, who praised its gritty naturalism and performances, particularly Pryor, whose Zeke learns a lesson about how crime and capitalism often go hand-in-hand. Its esteem has grown in recent years, with director Spike Lee placing it on his list of "Films All Aspiring Filmmakers Must See," alongside the title it's most often compared with, "On the Waterfront."

Girlfriends (1978)

You can see the influence of Claudia Weill's "Girlfriends" on just about any film that hopes to portray female friendship, from "Bridesmaids" to "Frances Ha" to the HBO series "Girls" (which Weill directed an episode of in 2013). What began initially as a 30-minute short funded by the American Film Institute morphed into an independently financed feature, one so impressive that Warner Bros. picked it up for distribution.

Melanie Mayron stars as Susan Weinblatt, a wannabe photographer making her living shooting bar mitzvahs and weddings. She shares an apartment in New York City with her best friend, aspiring writer Anne Munroe (Anita Skinner). Susan's life is thrown into turmoil when Anne decides to move out and get married, forcing her to face life on her own for the first time. Things are further complicated when she falls in love with a married rabbi (Eli Wallach) before finding her own boyfriend (Bob Balaban).

In an essay penned for the film's Criterion release, Molly Haskell wrote about what a landmark "Girlfriends" was in regards to stories of female friendships. Prior to that, "the buddies in conventional buddy films were invariably male. Women were still thought to be congenital rivals, incapable of bonding." And yet, "working outside the constraints of systematized storytelling, Weill recognized and captured the ways in which women's friendships were both similar to and different from love affairs, yet certainly every bit as complex — and probably more so." Critics praised the film, which Variety called, "a warm, emotional and at times wise picture about friendship."

Straight Time (1978)

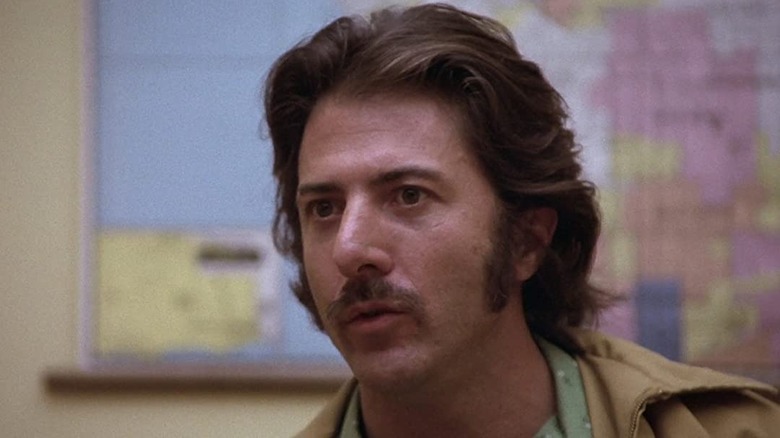

Dustin Hoffman began his career with 1967's "The Graduate," which, along with "Bonnie and Clyde" the same year, helped pave the way for the New Hollywood of the 1970s. Hoffman quickly became one of the era's favorite leading men, starring in such classics as "Midnight Cowboy," "All the President's Men," and "Kramer vs. Kramer," for which he won his first Oscar. He also starred in a number of minor hits that have since become canonized, including this gritty crime thriller that was originally intended as his directorial debut (he stepped down and Ulu Grosbard took over).

"Straight Time" centers on Max Denbo (Hoffman), a career criminal who decides to go straight after a stint in prison. But endless abuse from his parole officer Earl (M. Emmet Walsh) and a menial job at a canning factory begin to wear on him, and he soon finds himself falling back into a life of crime. The stacked supporting cast includes Theresa Russell as Max's new girlfriend, Jenny, Gary Busey as his drug addicted friend Willy, and Harry Dean Stanton as his criminal cohort, Jerry.

Based on the novel "No Beast So Fierce," Hoffman plays a fictionalized version of its author, real-life bank robber Eddie Bunker. A Hollywood character for decades, Bunker would go on to write and appear in films like 2000's "Animal Factory" (and consult on films like ""Heat"), famously playing Mr. Blue in "Reservoir Dogs."

"Straight Time" was a critical hit, with Vincent Canby of The New York Times calling it, "an uncommonly interesting film about a fellow whose significance is entirely negative." Even at the time critics were hailing it as a lost classic, with "At the Movies" hosts Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert including it on a special episode dedicated to overlooked films from the 1970s (along with "Sorcerer" and "Night Moves").

Real Life (1979)

As the 1970s came to a close, Hollywood studios began taking fewer and fewer chances on risky projects, opting instead for reliable concepts and carbon copies of previous hits. Directors with eccentric visions had to make their own way, leading to the independent cinema boon of the '80s and '90s. One talent who slipped into the business just in time was Albert Brooks, a standup comedian whose neurotic, self-effacing humor had made him a name via a series of short films (some for "Saturday Night Live"), leading to his directorial debut, the Paramount Pictures-produced "Real Life."

Brooks writes, directs, and stars in the film as — who else? — Albert Brooks, a comedian directing a documentary about an ordinary American family in Phoenix, Arizona. He follows the Yeager family — headed by veterinarian Warren (Charles Grodin) and his wife, Jeannette (Frances Lee McCain) — 24 hours a day, seven days a week with cameramen who are equipped with filming devices that resemble robotic diving helmets. But Brooks can't help but interfere with the Yeagers' lives in the hopes of creating a greater "reality," leading to hilarious consequences. In the decades since, many have credited the film (which was spoofing the landmark PBS docuseries "An American Family") with foreseeing reality TV long before it would proliferate American airwaves.

Critics at the time were rapturous, save for Roger Ebert, who called it "a great idea" which "fails so miserably that it lets its audience down." Yet Janet Maslin of The New York Times declared it an "often very witty assault on manners, moviemaking, an allegedly typical American family and everything its members hold dear."