Things About Seinfeld Only Superfans Know

What's the deal with "Seinfeld"? For nearly a decade, it was one of the funniest shows on TV. Now, all these years after it ended, millions of fans still quote its unique brand of observational humor word-for-word. The classic show has warped the English language so completely that many folks may not even realize they're doing it.

It broke all the rules of the sitcom format, changing them in the process. Before "Seinfeld," sitcoms relied on high-concept wackiness and rigid three-act structure. But these plots took a backseat to whatever was funniest in the moment, sometimes remaining unresolved as the credits rolled, and that's if there was any plot at all — "Seinfeld" is, after all, famously a show about nothing. It broke every taboo about what you could say on television, often, hilariously, just by never actually admitting they were talking about it ("He took it out?" "He took it out.").

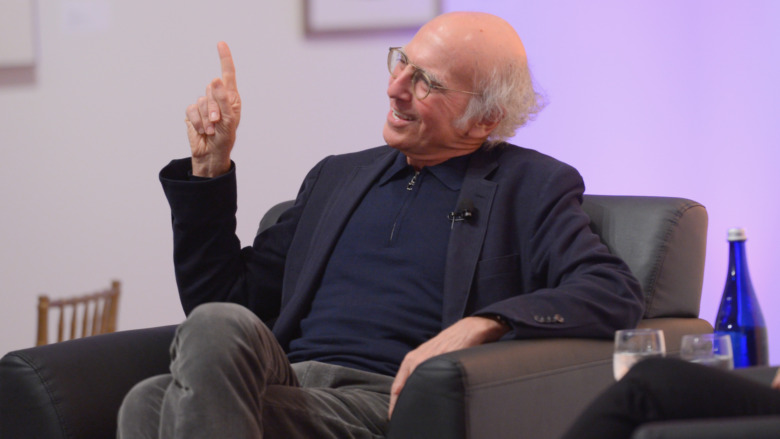

Most of all, before "Seinfeld," sitcoms depended on lovable characters and sloppy, sappy sentiment to keep viewers tuned in. But creator Larry David famously had a "no hugging, no learning" policy. That meant his characters — stand-up comedian Jerry, his loser buddy George, professional woman Elaine, and all-around weirdo Kramer — were free to destroy their own lives and everyone else's, and viewers around the world still loved them for it. Many of them have devoured every episode dozens of times. But there's always more to discover, and we've been able to find some things about "Seinfeld" that even the superfans don't know.

The real-life Kramer

Larry David famously based his show's breakout character Cosmo Kramer on a real-life neighbor named Kenny Kramer.

In "Seinfeldia: How a Show About Nothing Changed Everything," Jennifer Keishin Armstrong records the lengths David went to so he could use the name. The real Kramer played hardball, demanding financial compensation and even a chance to play himself. David and Seinfeld tried to work around it with other possible names (including "Kessler," which actually snuck into the pilot special) but none of them captured Kramer quite like "Kramer." So they finally struck a deal — Kenny Kramer would get his royalties, but they were able to talk him out of acting and give the role to David's "Fridays" costar Michael Richards instead.

But Armstrong also mentions another detail that makes it clear David found inspiration a little closer to home. Like Cosmo Kramer, Kenny Kramer had a tendency to drop in unannounced and raid David's fridge, but David was no slouch at mooching himself. The book reveals David hated grocery shopping and doing dishes so much he threw everything out of his kitchen except for one fork, one plate, and one spoon. He got everything else from Kramer, but he took an unusual approach so he wouldn't feel like he was stealing outright. He promised to pay Kramer back — and to keep up to his promise he'd keep a detailed log dividing the price of any box of food by the percentage of it he'd eaten.

"Seinfeld" resurrected Pez

"Seinfeld" became the biggest show on TV in the second half of its run, but it barely survived the first few seasons, which it spent constantly perched on the brink of cancellation. By Season 3, Seinfeld's cultural clout was beginning to become apparent.

One episode, "The Pez Dispenser," is, as you might have guessed, about a Tweety Bird Pez dispenser that makes Elaine burst out laughing in the middle of a piano recital. Those little plastic containers are omnipresent now, with new variants coming out for every holiday and major kid-friendly movie.

But in the series "Inside Look: 'The Pez Dispenser'," Jason Alexander claims that the candy company wasn't doing too well before the episode aired. But afterwards, "I wish I had taken stock! Pez was back on top! ... We took a relatively dead, obscure product, and that was very notable because I think that may have been the first time where you really saw something we were just goofing around with on the show suddenly have a rebound in the world."

Monk's diner inspired a pop hit

Nearly every episode of "Seinfeld" features a scene in the gang's favorite hangout, the iconic Monk's diner. Armstrong writes about how the "Seinfeld" crew scouted around New York for the perfect diner, and eventually found it in the Upper West Side in Tom's Restaurant. Greek immigrant Minas Zoulis' small family business was an unexpected candidate for international fame, but by the time "Seinfeld" moved in, Tom's had already found it once before.

Aspiring singer-songwriter Suzanne Vega was a frequent visitor to Tom's during her time at nearby Barnard College. She turned one rainy day in the restaurant into the a capella folk song "Tom's Diner" and released it on the "Fast Folk Musical Magazine" anthology in 1984 before adding it to her album "Solitude Standing" three years later. Then, in 1990, techno duo DNA took it to #5 on Billboard by adding their own beat and turning Vega's offhanded "doo doo doo" from the end of the song into a true pop earworm.

Even after "Seinfeld" brought millions of tourists his way, Zoulis never let his twofold fame go to his head. He refused to update Tom's, and turned down offers to sell or franchise the suddenly hot commodity. "You can sit down, you can have a cup of coffee, you leave here with your wallet intact," he said. "What more could you ask for? It's not like we were seeking fame and fortune."

Larry David had an understated way of putting down pitches

Much like Jerry Seinfeld himself, Larry David put his unique personality into "Seinfeld," and reading some of Armstrong's stories about him, it's hard not to imagine him as a character on the show. Jason Alexander famously complained to him that one plot — where George makes a dramatic exit from his job, regrets it, and shows up the next day as if nothing happened — was unrealistic. David responded, "What are you talking about? That happened to me and that's exactly what I did!"

David brought a deeply Jewish, deeply New York sense of understated, sarcastic wit to the series, along with a good chunk of his own life story. One of Armstrong's stories sums it up best. The other writers had to pitch their ideas to him before they could go ahead, and David was difficult to please but gentle in his putdowns. If he hated an idea, he'd simply say, "No, I don't love that one." And if he really hated it, he'd say, "I could see that on another show" — which sounds nice, but becomes downright scathing when you read between the lines.

One live audience member asked if she was watching a rerun

"Seinfeld" followed a tradition dating back to the days of radio by inviting a live studio audience to watch the crew at work. Before the show took off, the studio needed to recruit volunteers to fill the seats. Later, getting tickets became a competitive endeavor, but no matter how big the show got, they were always free.

The audience helped liven up the show, but they caused their own set of problems. Their applause for Kramer's entrance every week ate up so much time, for instance, that the producers finally had to tell them to stop.

As many shows do, "Seinfeld" often invited a comedian to "warm up" the audience before the taping. Not everyone in attendance understood the process, however. Armstrong quotes one warm-up comedian, Pat Hazell, who remembers an old lady asking him before the performance started if it was going to be a rerun. For the rest of the show, Hazell kept popping in to ask her what happens next.

A producer auditioned to play himself — but didn't get the part

The show's break-out season transformed it into must-see TV, while also introducing a yearlong arc that most producers would have rejected as too sophisticated for the average boob tube enthusiast. Jerry and George try to sell a pilot for "Jerry," their "show about nothing," inspiring a coffee shop conversation nearly identical to the one Armstrong writes led to the real-world "Seinfeld."

The real show started out with an aspiring producer named Jeremiah Bosgang as their network liaison. According to Armstrong, by the time "Seinfeld" began its fourth season, Bosgang had moved on to Fox, when he got a call from an actor friend who'd just auditioned to play Jeremiah Bosgang. He got "Seinfeld" producer George Shapiro on the phone, who explained the new season's meta plotline. Bosgang asked for the part, and Shapiro got him an audition. "Wait a minute," Bosgang said. "I have to audition? For Jeremiah Bosgang?"

Bosgang drove across town to the NBC studios. He signed in with the receptionist, much to her confusion, and read for the part. In the end, Jeremiah Bosgang's many years of experience as Jeremiah Bosgang weren't enough. The "Seinfeld" writers renamed the character Jay Crespi and gave it to actor Peter Blood.

Jerry Stiller created Frank Costanza's personality by accident

"Seinfeld" has a core cast of four regulars, but it also has a memorable stable of recurring guests, none more memorable than Jerry Stiller as George's irascible dad Frank Costanza. He's the ultimate bad dad, and watching him play off of Estelle Harris as his wife, it's easy to see how George ended up the way he did.

While a character with his ... peculiarities ... could be excruciating to watch, Stiller made him endlessly entertaining with his unique cadence and seething rage, selling some of the show's most classic plots like his inventions of Festivus, the "mansiere" and, of course, "Serenity now!"

Stiller's performance is a work of comic genius, but it came about almost by accident. Jason Alexander explained to "The Kevin Pollak Chat Show" that "the whole Frank Costanza milieu is Jerry Stiller remembering his lines about three and four words at a time. He would begin it and then he wasn't sure where it was going and he would get scared and frustrated and so then all of a sudden a hostile reading came out, not of him making a choice, it came out of his frustration with himself ... It's this psychotic, desperate grab for the next four words that fueled that character."

The writers had a unique suggestion for NBC's 1994 crossover

One of the most important elements in the success of "Seinfeld" was total creative freedom. From the beginning, David and Seinfeld had unprecedented leeway to follow their muses against all the rules of sitcom TV. This meant they were the only sitcom not to participate in NBC's Thursday Night Blackout crossover in 1994.

Since Thursday nights were a solid two-hour block of New York-based comedies, one producer came up with the idea of putting all four casts through a city-wide blackout. It started on "Mad About You," where Helen Hunt's character Jamie accidentally knocks out the power grid while she's fiddling with the cable, leaving the casts of "Friends" and the short-lived "Madman of the People" in the dark. Sandwiched in the middle was "Seinfeld," where everyone's power worked just fine.

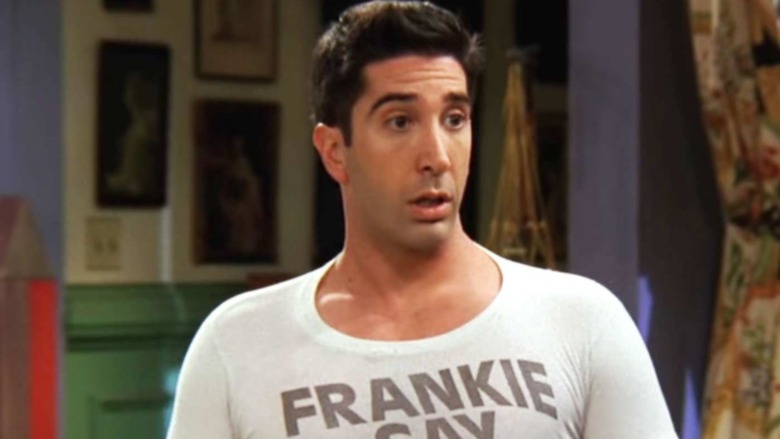

That's because none of the show's producers had any interest in a plot conceit they dismissed as a gimmick. One of them had an idea of his own, though, that might have been more entertaining: Armstrong quotes "Seinfeld" writer/producer Peter Mehlman, who suggested to Larry David: "You know, we could have, like, the David Schwimmer character from 'Friends' on our show, and we could kill him! Like, he dies! We should really consider this." Undoubtedly, millions of Ross and Rachel fans are thankful "Seinfeld" never got their hands on Schwimmer.

The show drove the real J. Peterman to bankruptcy

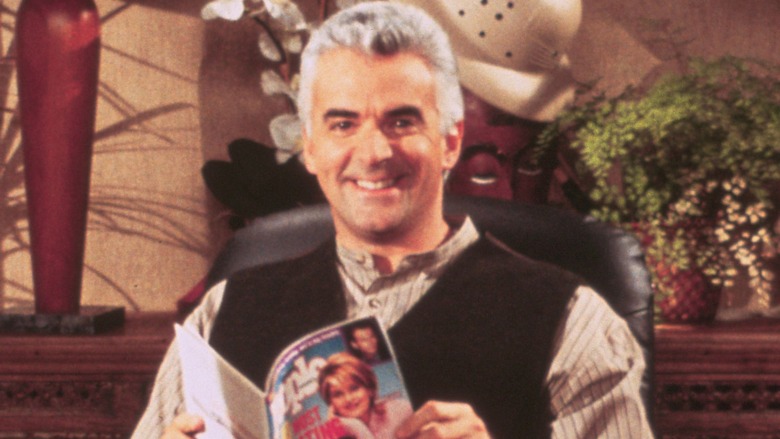

"Seinfeld" introduced yet another colorful side character in Season 6's "The Understudy," where Elaine goes to work writing catalog descriptions for the J. Peterman menswear company. Her eccentric, larger-than-life boss Jacopo Peterman was based on the real John Peterman — or, more accurately, on what the writers imagined he must be like based on the grandiose copy in the real J. Peterman catalogues.

Far from being insulted, the real Peterman was thrilled with the sudden influx of free publicity and according to Armstrong, he enjoyed hanging around the set with his "Seinfeld"-universe counterpart, John O'Hurley.

Unfortunately, Peterman severely overestimated how much good his newfound TV fame would do him. He decided this was the moment to expand into in-person retail locations, with plans for up to fifty new stores. Even with his increased name recognition, the demand couldn't live up to Peterman's dreams, and he eventually filed for bankruptcy, claiming a debt of $14 million.

Entrepreneur magazine reports that Peterman had to sell out to Paul Morris Stores. But after they went bankrupt, Peterman bought his name back and revived the J. Peterman catalogue — online this time, but with no less colorful product descriptions.

Phil Morris had inside experience with his Johnnie Cochran impression

When the "Seinfeld" writers prepared a script for Kramer's lawsuit against a coffee shop in "The Maestro" (Season 7, Episode 3), they wanted a lawyer who could match the character's cartoon energy. In 1995, there was only one character who could fit the bill, and he was a real-life one seen regularly on TV.

Johnnie Cochran had become a celebrity as recognizable as any actor for his role defending former quarterback O.J. Simpson against murder charges. His larger-than-life persona and wordplay ("If the glove doesn't fit, you must acquit!" "If it doesn't make sense, you should find for the defense!") were burned into the minds of TV viewers. So, "Seinfeld" introduced its own version of Cochran with Phil Morris as Jackie Chiles, who would return five more times before the show ended, including a key role in the final episode.

In the behind-the-scenes series "Inside Look: 'The Maestro,' Morris explains why he was the man for the job. "I've known Johnnie Cochran since I was a little kid! We've gone to the same barbershop in L.A. since I was about seven or eight years old ... not having any clue that I was kind of doing subliminal research on him."

Larry David lived to regret quitting "Seinfeld"

Larry David left "Seinfeld" behind in 1996, resulting in two David-free seasons. Armstrong writes the days after his departure were tough for David, as he tortured himself with worries that he'd thrown away the best opportunity he'd ever had and began resenting the show for continuing on without him.

Not helping matters, David returned to the "Seinfeld" set periodically to record his lines as George's boss, New York Yankees owner George Steinbrenner. Adding insult to injury, he got stopped at the gate and even after he gave his name, the guard had to call the office for permission to let David in while he silently shouted to himself, "Don't you understand? See that show? I created that thing!"

David eventually worked through his regrets and found new success as the creator and star of HBO's iconic "Curb Your Enthusiasm." But he learned from his experience. When his friend Aaron Sorkin left his own show "The West Wing," David told him never to watch it again. "Either it's going to be wonderful and you'll be miserable, or it won't be wonderful and you'll still be miserable."

The real Festivus was equally bizarre

With "The Strike" (Season 9, Episode 10), we were introduced to Festivus, an eccentric alternative Christmas dreamed up by Frank Costanza and now celebrated across the country. It's one of the series' zaniest episodes, and if you're feeling uncharitable you might even call it unbelievable. But don't — not only did the writers take Festivus from real life but if anything, they toned it down.

"I did not pitch Festivus as an episode," writer Danny O'Keefe says in "Inside Look: 'The Strike.'" "In fact, I had totally blocked it out of my mind."

O'Keefe was the son of anthropologist and Reader's Digest editor Daniel O'Keefe, Sr. His coworker Jeff Shaffer describes the O'Keefe family as "rich in insanity"; in "Seinfeldia," O'Keefe himself calls Festivus a "strange piece of psychodrama." There were no Feats of Strength, but there was an Airing of Grievances. There was no pole, but there was a clock, a bag, and a cardboard sign reading "F*** fascism!" Why? Not even O'Keefe knows.

Carols included an Irish folk song about hanging a bomber and quacks to the tune of "The Nutcracker Suite." It also wasn't a Christmas alternative like Costanza's Festivus: O'Keefe says, "It didn't really have a set date, which made it all the more ominous ... We were given very little notice."

One of Seinfeld's funniest episodes cut one of its funniest lines

The final season of "Seinfeld" had the series getting more inventive than ever.

"The Betrayal" (Season 9, Episode 8) not only takes Jerry, George, and Elaine all the way to India, it doesn't explain how they got there until later. Inspired by Harold Pinter's play "Betrayal," the entire story is told in reverse, beginning with the aftermath of a disastrous wedding that Elaine ruins by revealing she'd slept with the groom years earlier, and ending with Jerry moving into his apartment and meeting Kramer for the first time. Along the way, we learn that Elaine only came to the wedding to spite the bride, her longtime nemesis Sue Ellen Mischke, before learning she's the Maid of Honor.

"The Betrayal" is as packed with hilarity as any "Seinfeld" episode — so much so, in fact, that they didn't have room for a joke most other series would kill for.

On the audio commentary, writers Peter Mehlman and David Mandel reveal they cut a conversation from the script between George and the usher at the wedding:

"Are you with the bride or the groom?" the usher was supposed to ask.

"We're spite," George would reply.

"Oh," the usher would shoot back. "You can sit wherever you want."

If those lines had made it to air, could it have joined the long line of quotable "Seinfeld" phrases like "Yada yada," "Hello, Newman," and "Not that there's anything wrong with that"? We may never know, but it's a testament to the show's quality that even jokes that good weren't good enough to make it into the classic show.