False Facts About Hayao Miyazaki You Thought Were True

With a career lasting over half a century and directing credits on some of the most beloved films of all time, Hayao Miyazaki has more than earned his status as a legendary figure in the world of animation and cinema. Yet by definition, a legend involves some twisting of the facts, and the Miyazaki who exists in fans' imaginations doesn't always match with the flesh and blood human being still at work developing new movies at Studio Ghibli.

Myths and misconceptions about the filmmaker can come from very different places. Sometimes memes about Miyazaki take on a life of their own beyond their initial usage, while other assumptions about him stem from judgments that might seem realistic based on his films and studio but don't always reflect his own beliefs and behavior. This article will take a look at the most commonly believed falsehoods about Hayao Miyazaki, identifying where these false facts came from and if they are in any proximity to the actual truth.

Myth: He said anime was a mistake

In all fairness to anyone who may have believed that Hayao Miyazaki said the phrase "Anime was a mistake," it isn't entirely off the mark from many things he has said, as the director is known for speaking his mind. Miyazaki has shown zero reluctance to criticize aspects of the anime industry he dislikes, particularly the way otaku (or obsessive fan) driven anime draws more inspiration from other anime than from real life, and he has attempted to distance the works of Studio Ghibli from the "anime" label as a result. In spirit, the memes of Miyazaki calling anime a mistake are based on something real, even if he didn't say this verbatim.

Even so, it's worth noting that this quote often attributed to Miyazaki is a humorous fabrication. It originates from a 2015 Tumblr post on the blog old-Japanese-men. The meme took a scene from the documentary "The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness" where Miyazaki did complain about otaku — a scene the doc ironically juxtaposes with Miyazaki completely geeking out over toy planes with his "otaku" protégé Hideaki Anno — and changed the subtitles into the exaggerated meme we know and love today. So yes, you can continue making "anime was a mistake" jokes, but with the knowledge that this is a meme and not the actual words of Miyazaki.

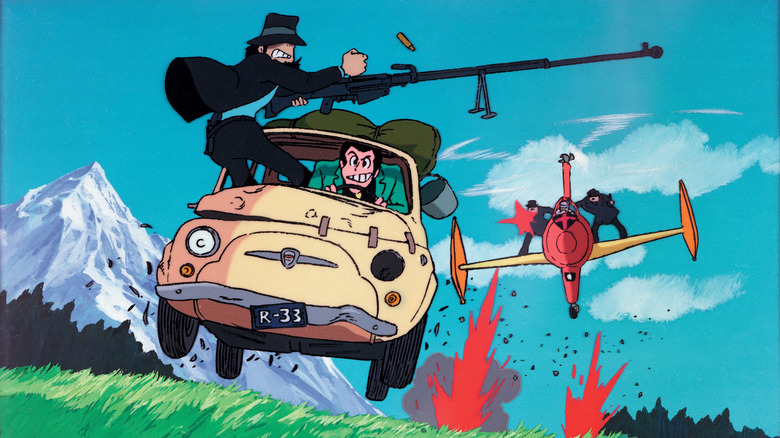

Myth: Miyazaki's first film inspired Indiana Jones

On the cover of Manga Entertainment's home video releases for Hayao Miyazaki's 1979 debut film, "Lupin III: The Castle of Cagliostro," there's a quote attributed to Steven Spielberg calling it "one of the greatest adventure movies ever made." Curiously, though, there's no record of Spielberg ever saying this about the film anywhere except this box art. When Discotek rereleased "The Castle of Cagliostro" on Blu-ray, they were unable to find any source for the Manga Entertainment quote. Further digging seems to suggest it was made up for an amateur publication at the 1986 BayCon anime convention.

If Spielberg has seen "The Castle of Cagliostro," it does seem like a movie he would appreciate — he's highly praised other Miyazaki films such as "Spirited Away," and it is a rollicking adventure film comparable to the "Indiana Jones" movies. The urban legend that "The Castle of Cagliostro" directly inspired "Indiana Jones," however, is almost certainly impossible. "Raiders of the Lost Ark" had already started filming in the summer of 1980 at the time "The Castle of Cagliostro" was having its first English-subtitled screenings to mostly empty rooms at science fiction conventions. Miyazaki's movie wouldn't get an official American release until 1991 after Spielberg had already completed his first three "Indiana Jones" installments. Miyazaki, for his part, is not a fan of the "Indiana Jones" movies, criticizing their violence and racial implications.

Myth: Miyazaki had darker intentions for Totoro

There are seemingly few things the internet likes more than taking media intended for kids and twisting it with dark and edgy fan theories. Along with "Ponyo," "My Neighbor Totoro" is the Hayao Miyazaki film most directly made with young children in mind — so naturally it's been the subject of the most ridiculous theories. People online have claimed that Totoro isn't a forest god but a death god, that Mei and Satsuki end up dead (pointing to their lack of shadows in the very last scene as evidence), and that the film is based on the 1963 "Sayama Incident" murder case.

The theory has become popular enough that Studio Ghibli had to make an official statement debunking it. If you want to find darkness in "My Neighbor Totoro," you can always focus on the elements that are already in the film — "My Neighbor Totoro" is able to touch on fears of mortality through the ongoing issue of the mother's illness and the anxiety in the sequence when Mei goes missing. And it does this without having to kill off any characters or evoke a grisly true crime. Darkness exists in Studio Ghibli films — you needn't look further than "Grave of the Fireflies" — but "My Neighbor Totoro" remains a feel-good classic.

Myth: Miyazaki hates CGI

Hayao Miyazaki's continued dedication to the art of traditional hand-drawn animation is a big part of his work's appeal, especially with computer animation completely dominating the market in the United States. He prefers working by pencil and doesn't even have a computer of his own. This preference for 2D animation, however, is sometimes misinterpreted as equating to a hatred of 3D animation, which just isn't the case.

Every Miyazaki film since 1997's "Princess Mononoke" has involved some degree of CGI effects blended in with the hand-drawn work. His 2016 short film "Boro the Caterpillar," made exclusively for the Ghibli Museum, had a CG main character. Miyazaki has praised the works of Pixar, with Ghibli even licensing a Totoro toy to appear in "Toy Story 3." Perhaps most surprisingly, he's reportedly one of the only people to praise the computer animation in his son Goro Miyazaki's film "Earwig and the Witch."

It seems the video most commonly pointed to as evidence of Miyazaki "opposing" computer animation is a scene from the 2016 documentary "Never-Ending Man: Hayao Miyazaki" where he digs into a computer animation test, calling it "an insult to life itself" (via YouTube). But there's an important distinction to note here: this animation test wasn't merely animated using computers, but entirely generated by an artificial intelligence program. Opposing AI is very different from opposing CGI crafted by human artists.

Myth: Miyazaki is against doing sequels

This is a myth Hayao Miyazaki might want people to believe, to the point a 2023 profile in The New York Times Magazine that otherwise rejected major myths about him reiterated this one uncritically. The fact Miyazaki has avoided making feature-length sequels (he made a "My Neighbor Totoro" short film sequel titled "Mei and the Kittenbus" exclusively for the Ghibli Museum) gives him hipster credibility in a culture where it seems every original idea gets wrung dry by franchising. Yet it's dishonest to ignore how Miyazaki wanted to make sequels at least once — and possibly more times — in his later career.

Miyazaki initially wanted to follow up "Ponyo" with a sequel before his producer Toshio Suzuki convinced him to adapt his manga "The Wind Rises" into a movie instead. Around the same time, rumors spread that Miyazaki was developing a sequel to "Porco Rosso," called "Porco Rosso: The Last Sortie." It's not clear whether this was meant as a movie or a manga, with Miyazaki describing the idea as an "old man's hobby" (via Collider), though a 2011 Guardian interview with Hiromasa Yonebayashi mentioned it as being in the works.

Additionally, though Miyazaki has expressed no interest in making a movie sequel to "Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind" himself, he has reportedly given his blessing to former Ghibli animator and "Evangelion" creator Hideaki Anno to make a sequel based on the manga series. Anno made a live-action "Nausicaä" prequel short titled "Giant God Warrior Appears in Tokyo."

Myth: Miyazaki was opposed to streaming

When the Studio Ghibli library showed up on HBO Max in the United States and Netflix for the rest of the world in 2020, it came as a surprise. Just a year earlier, the official company line was that the studio was against digital distribution entirely, wanting to emphasize the theatrical experience. Hayao Miyazaki claims to be horrified by the idea of kids constantly rewatching his films on video, saying his films should be watched once a year at most (via The New Yorker), so it makes sense people would assume this anti-streaming position came from Miyazaki.

However, there's one little detail preventing Hayao Miyazaki from taking a hardline anti-streaming stance: he's so out of touch regarding modern technology that he doesn't even know what streaming is. It's possible Miyazaki would oppose streaming his films if he knew the details, so Ghibli's former stance makes sense from that logic. However, Toshio Suzuki claims Miyazaki was easy to convince to approve the deal with HBO and Netflix because he didn't particularly care to know the details beyond the fact it would make the studio enough money to finish its upcoming film, "The Boy and the Heron."

Myth: The Boy and the Heron's lack of promotion was Miyazaki's idea

When "The Boy and the Heron" was first released in Japanese theaters, there wasn't a single piece of advertising for the film except for one poster showing a close-up of the heron. It was an audacious minimalist non-marketing strategy and only a filmmaker as legendary as Hayao Miyazaki could get away with it. Since the initial release, more images from the film have been made available for publicity, and the American theatrical release has received traditional trailers.

Some fans have been strenuously trying to avoid this marketing, believing it infringes on the purity of the Japanese strategy. But this strategy might not be so much an act of artistic purity as one of economics: "The Boy and the Heron" is reportedly the most expensive Japanese film in history, so having no marketing on a film that theoretically sells itself in its home market saves a lot of money. Despite helming the film, this strategy wasn't cooked up by Miyazaki. It was all Toshio Suzuki's idea, and while Miyazaki went along with the unusual idea on trust, he privately expressed worry about the idea of not doing publicity.

Myth: Hayao Miyazaki opposed rides at Ghibli Park

Hayao Miyazaki and Studio Ghibli are intertwined in the public eye, and so when Studio Ghibli makes an unusual decision, there's a tendency to attribute such decision-making to the studio's star director even if he wasn't involved. One notable example of this regards Ghibli Park, an amusement park in Aichi, Japan where traditional rides are completely forgone in favor of art installations coexisting with nature. The park is a fitting reflection of the relaxed pace and environmentalist themes of many of Hayao Miyazaki's films, so it would seem logical to assume this idea came from the director — except it didn't. In fact, it's in opposition to what he was looking to do.

It's actually Goro Miyazaki who is in charge of designing the park (he was an architect well before he was a director), and it was Goro's decision to make a park without rides. Hayao actually had visions of a park more like Disneyland and spent time drawing designs for Ghibli-themed roller coasters. His son rejected all those plans, believing such rides couldn't capture the experience of the studio's films. As reported in The New York Times Magazine, Hayao Miyazaki's ultimate impression of Ghibli Park was that it "was something that I wouldn't have come up with myself."

Myth: Miyazaki attended the opening of Ghibli Park

How many directors are both popular and instantly recognizable enough that fans can cosplay them? And how many of these cosplayers manage to do it convincingly enough that they trick the public into thinking they're the real deal? On November 1, 2022, at the opening of the Ghibli Park, a Japanese TV news report went viral on X, formerly Twitter, showing what looked to be Hayao Miyazaki casually strolling by the park entrance.

Alas, such an occurrence was too good to be true — though the actual truth of the situation was even funnier. It turns out a cosplayer going by the name Izumi Pao has been doing impersonations of Miyazaki for 15 years. In close-up pictures of Pao's Miyazaki cosplay, it's obvious that the beard and eyebrows are fake, but Pao gets into character so effectively that from a distance he's easy to mistake for the real deal.

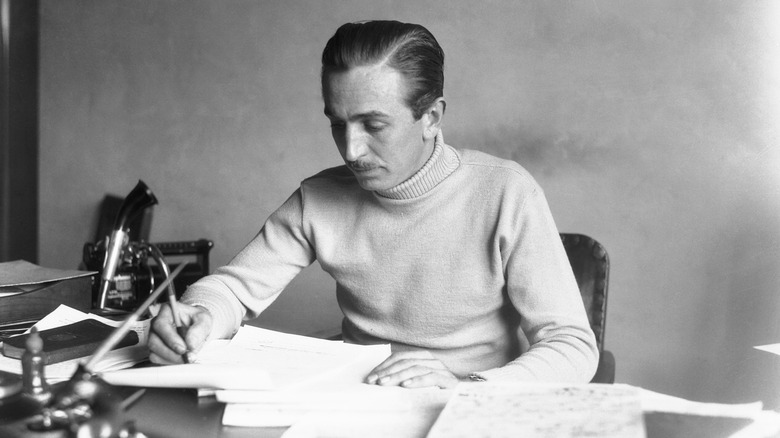

Myth: 'The Disney of Japan'

This is a bit more subjective than other claims on this list. It's true that there are fair grounds to compare Walt Disney and Hayao Miyazaki in terms of cultural impact and popular acclaim. But it would be wrong to think Miyazaki himself appreciates this comparison. Though Miyazaki has at times voiced begrudging appreciation for some of Disney's work, for the most part, he seems to flat-out hate Disney.

In the essay "Thoughts on Japanese Animation," collected in the book "Starting Point: 1979-1996," Miyazaki stated, "I must say that I hate Disney's works, the barrier to both the entry and the exit of Disney films is too low and too wide. To me, they show nothing but contempt for the audience." There are some classic Disney cartoons he likes: the 1937 short film "The Old Mill" is his favorite, and he reportedly acknowledged "Pinocchio" as great. But Miyazaki is less influenced by Disney and more influenced by the Fleischer brothers, Russian animators like Yori Norstein and Lev Atamanov, and Paul Grimault's "The King and the Mockingbird."

Miyazaki has had a complicated relationship with the company bearing Walt's name. He ranted against Disney in the '80s, but in the '90s agreed to let them distribute Ghibli's films internationally on the condition they get released uncut. Disney no longer distributes Ghibli films in the U.S. but still handles Japanese DVD releases — and Ghibli made a Grogu short for Disney+.

Myth: 'A guy who makes such happy movies must be a happy person'

How would you describe Hayao Miyazaki's personality? Casual fans whose knowledge of the man comes from watching his films and maybe seeing the occasional inspirational quote of his on social media would likely answer this question very differently from those who have read interviews with or seen documentaries about the man. The truth of Miyazaki is that, even if his movies deliver happiness and hope, Miyazaki himself consistently comes across as weary, miserable, and difficult to work with.

Here's a man who sees modern life as "thin and shallow and fake," welcoming financial disaster and apocalypse if it means the natural world claims dominion over humanity (via The Asia-Pacific Journal). Some of this negativity is an understandable extension of his high moral ideals, but Miyazaki himself doesn't always meet such ideals: He was absent as a father, and horror stories abound about what it's like to work under his perfectionistic demands — even his friend Hideaki Anno describes him as "a really mean old guy" (via GQ).

Miyazaki's films, for the most part, are an attempt to deliver positivity to children that he knows he doesn't have much of himself. Speaking at the Paris press conference for "Spirited Away," he explained this philosophy: "I am a pessimist. But when I'm making a film, I don't want to transfer my pessimism onto children ... children are very much capable of forming their own visions. There's no need to force our own visions onto them" (via Midnight Eye).