The Ending Of Take Care Of Maya Explained

The following article includes allegations of child abuse and a discussion of suicide.

Most parents want to do everything they can to keep their children safe, happy, and free from suffering. But for too many families living in the U.S. today, the systems that are supposed to protect them end up failing them, and when they do, the consequences can be devastating. It's a failure that's central to the tragic tale at the heart of the Netflix documentary "Take Care of Maya."

Through depositions and interviews, the documentary explores how the convergence of health care, the judicial system, and human services allowed one family's ailing young daughter to be indefinitely detained in a hospital after her mother's efforts to advocate for her care were labeled medical abuse. The film outlines how desperation at Beata Kowalski's inability to stop her daughter Maya's suffering or even hug her child would ultimately lead to Beata's tragic death.

A tale both frightening and hopeful, "Take Care of Maya" serves as a dire warning against bias and unquestioned authority. Here's everything you need to help you unpack the ending of the documentary.

What you need to remember about the events of Take Care of Maya

Before they would come into conflict with the medical and judicial systems, the Kowalskis were a typical American family. A strong-willed Polish immigrant who "never took no for an answer," Beata had worked hard to teach herself English before going through college and nursing school. Despite some initial challenges, Beata and her husband Jack were thrilled to welcome their daughter Maya. According to Jack, Beata was a loving parent who poured herself into motherhood. By the beginning of 2015, Beata was working as a home care infusion nurse while Jack was enjoying the benefits of retirement from his career as a firefighter. From their idyllic home to their beautiful family, Jack described their life as a "dream come true. Paradise."

It was around that time that young Maya's health began to decline. According to Maya's deposition, she began experiencing severe pain in her extremities. "Her skin felt like it was on fire," Jack reflected. She became extremely lethargic with blurred vision, headaches, lesions, difficulty moving, and dystonia in her legs. After cycling through unhelpful doctors, Maya was eventually diagnosed with Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS), finding relief in high doses of ketamine under an anesthesiologist's care. But when a relapse led to an emergency room visit where doctors did not understand the condition, Beata found herself the target of a child abuse investigation, barred from any contact with her daughter as Maya suffered alone in the hospital for months.

If you or someone you know may be the victim of child abuse, please contact the Childhelp National Child Abuse Hotline at 1-800-4-A-Child (1-800-422-4453) or contact their live chat services.

What happened at the end of Take Care of Maya

Beata's experience as a medical professional had taught her to meticulously document everything, as the frustrated parents took Maya from one doctor to the next seeking a diagnosis. A tireless advocate for her child, Beata was unwavering in her commitment to Maya's health. But it was this commitment that the child welfare system would use as evidence that Beata was exhibiting Munchausen syndrome by proxy, fabricating claims of Maya's illness and intentionally keeping her ill.

When the medical staff initially encountered the Kowalskis in 2016, they found Beata's insistence on ketamine treatment alarming — particularly given their lack of training about CRPS — and they began to doubt the diagnosis. Child Protective Services called in physician Sally Smith, who swiftly removed Maya from her parent's custody. As Maya's parents fought to get her back, a judge barred the hospital from administering ketamine treatment. For months, the frightened Maya suffered alone as doctors failed to treat her symptoms. Every effort Beata made to save her daughter was turned against her until she was banned from even speaking to or hugging her child. It was only after the despondent mother died by suicide that Maya was released back to her father's care. Today, the remaining Kowalskis' efforts to hold Johns Hopkins All Children's Hospital accountable are still tied up in court with no end in sight.

If you or someone you know needs help with mental health, please contact the Crisis Text Line by texting HOME to 741741, call the National Alliance on Mental Illness helpline at 1-800-950-NAMI (6264), or visit the National Institute of Mental Health website.

If you or someone you know needs support now, call or text 988 or chat 988lifeline.org.

What the ending of Take Care of Maya means for the survivors

For Maya, the impact of her months-long separation from her family had to be immeasurably terrifying and lonely, and she was never given a chance to say goodbye to her mother before the initial separation was imposed. As Maya would explain in her deposition, depriving her of her support system, physical therapy, and a proper treatment plan made it "almost impossible to improve." She would also recount that although she constantly engaged with medical professionals, none of them listened to her. The lasting impact of this medical trauma makes it difficult for her to see doctors today despite her ongoing battle with her severe health condition.

Throughout the fear, loneliness, and pain, Maya desperately yearned to see her mother again. It's hard to imagine the world-shattering heartbreak she felt when she learned that her mother had died by suicide, a loss she and her family carry with them today. Although nothing can bring Beata back, the surviving Kowalskis want the world to know that despite Sally Smith's accusations, Beata was an amazing mother who fought bitterly for her child's life.

Take Care of Maya is a rebuke of failures in the U.S. healthcare system

Like many patients suffering in the U.S. healthcare system, Maya's road to diagnosis was plagued with blind spots, tunnel vision, and an overall lack of communication between medical professionals. As the family bounced from one specialist to another, the medical experts she encountered seemed intent on considering only the conditions they were familiar with. And all too often, they dismissed Maya's symptoms as psychosomatic or hyperbolized despite Beata's extensive documentation of her daughter's skin lesions, pain, and other health problems. This myopia is evidenced in a 2015 video recording Beata taped with Maya's immunologist, who chastised her, "A kid can tell you, 'I can't breathe.' How do I know she's not having an anxiety attack?"

Beata's refusal to accept this treatment led her to anesthesiologist Dr. Anthony Kirkpatrick, who recognized Maya's condition immediately as an advanced case of CRPS, a condition that could be fatal if left untreated. As a Hail Mary, the doctor recommended an experimental treatment that involved putting Maya in a six-day medically-induced coma followed by a regular regimen of ketamine doses. The treatment was successful enough that Maya was able to go back to school and resume a fairly normal life for a time. When she relapsed in October 2016, the ER refused to administer the dosage of ketamine Maya had been receiving as part of her care, and called Beata belligerent and demanding.

It's also about how the judicial system and child welfare systems fail families

As with many families under investigation for medical child abuse, Florida's child welfare and judicial systems worked in tandem to amplify the injustices experienced by the Kowalski family. The professionals who should have been working to help this family rushed to judgment in their assessments of Beata and Maya with little regard for the severe and lasting impact this could have on the family, particularly the child. As a state where the child welfare system is privatized, Florida's Department of Children and Families has the power to remove children by citing probable cause of harm to the child. According to attorney Debra M. Salisbury, who refers to the system as "the child welfare industry" in the documentary, children in Pinellas County are almost two and a half times more likely to be removed from their homes than in the rest of Florida.

An employee of Suncoast Advocacy Center — an organization contracted with Florida CPS — Sally Smith was called in to investigate Maya's case. Ultimately, Smith labeled it as a case of medical child abuse despite Dr. Kirkpatrick's efforts to explain Maya's condition to her and warn about the long-term damage to the family. According to Dr. Kirkpatrick, Smith omitted all this information from her report on Maya's case. As Smith moved forward with the case, CPS severely restricted Beata's access to her daughter. When the judge demonstrated bias in favor of CPS and hospital doctors, Beata was all but convicted.

Who is really to blame in Take Care of Maya? What experts say

In the documentary, Dr. Kirkpatrick blames the hospital for its refusal to treat Maya. "This was not the first time I've seen this type of scenario," he lamented. According to Kirkpatrick, hospital staff tend to reduce patients' ketamine dose after a few days of treatment despite their doctors' treatment plans. Without those higher doses, CRPS patients can begin to lose mobility in their legs, creating blood clots that can break off and end up in the lungs, potentially with fatal consequences.

In an email to Beata, Kirkpatrick did not mince words, asserting that the hospital's misdiagnosis of Beata "makes it easier for [Johns Hopkins] Children's Hospital to conceal their incompetence" surrounding Maya's care. It's also worth noting that during the initial court proceedings as part of Maya's sequestration, Beata was evaluated and found not to have Munchausen syndrome by proxy. Weighing in on Maya's case in Talking Disability, Neuroscience Research Australia (NeuRA) CRPS expert Dr. James McAuley emphasized the intangibility and invisibility of the disease add up to a "lack of public awareness surrounding CRPS," something that ultimately led to the false accusations against Beata.

Advocates accuse Sally Smith of medical kidnapping

Reflecting on her time under CPS custody, Maya likens her hospital stay to being held captive or medically kidnapped. She was even led to believe she would never return home. During Maya's time in state custody, social worker Cathi Bedy made a number of alarming statements, telling the girl her mother was in a mental hospital and that Maya would go into a foster home or Bedy would adopt her. Maya's case isn't the only time Florida CPS has been accused of medical kidnapping under the direction of Sally Smith. In 2021, a petition was created to appeal to Pinellas County CPS and the Florida Department of Health to fire Sally Smith for a similar case related to the children of "American Idol" finalist Syesha Mercado.

According to the petition, the then-pregnant Mercado and her partner took their son to All Children's after becoming concerned her breast milk production challenges were affecting their 15-month-old, only to have him taken from their custody under Smith's direction. Amid the couple's ongoing legal battle to get him back, CPS later took custody of their ten-day-old daughter after a welfare check. Speaking to the issue in an Instagram post featuring an image of Smith, civil rights attorney Lee Merritt urged, "The kidnapped children must be returned to their families and Smith must be terminated and criminally charged."

Physician Sally Smith continues to deny responsibility

Despite Maya's now well-documented diagnosis of CRPS, physician Sally Smith remains steadfast in her belief that she was correct in her initial assessment. As part of her deposition, Smith testified, "I presented the information to the best of my professional ability and came to a conclusion." But according to the Pensacola News Journal, Smith has a history of controversial professional behavior that involves "quickly diagnosing child abuse and ripping families apart by separating them despite many of the parents or caregivers being credibly innocent."

It's an allegation that's supported by USA Today's 2021 investigation of the doctor, who journalist Daphne Chen called "one of the most powerful figures in the child welfare system along Florida's Gulf Coast." According to Chen, All Children's Hospital calls Smith to investigate most suspected abuse cases, and prosecutors accept her conclusions implicitly. In their investigation, USA Today found that "more than a dozen" cases had been dropped with families suffering "irredeemable damage to their lives and reputations." Smith has been accused of traumatizing children like Maya while photographing them partially nude looking for signs of abuse. Parents also reported confrontations with Smith yelling or threatening foster care placement if they refused to acquiesce. Nonetheless, Smith has only doubled down on her decisions despite Suncoast settling her part in the Kowalskis' lawsuit for $2.5 million in 2023, telling The Cut, "To my knowledge, I don't have any cases where I've made an incorrect conclusion."

Johns Hopkins blames the child welfare system

The Kowalskis' trouble began when Johns Hopkins All Children's Hospital reported them for child abuse. Like Sally Smith, Johns Hopkins has been quick to deny any culpability in the Kowalski tragedy, with a spokesperson telling People, "Our first responsibility is always to the child brought to us for care, and we are legally obligated to notify the Department of Children and Families (DCF) when we detect a sign of possible abuse or neglect. It is DCF that investigates the situation and makes the ultimate decision about what course of action is in the best interest of the child."

As in most states, medical professionals are designated mandatory reporters by law, which means they are legally required to report any suspected child abuse to the authorities — something they do frequently despite Florida's troubled child welfare system. But many critics of the hospitals' actions believe they should have done more to explore the possibility of a CRPS diagnosis and to reach out to an expert in the condition, particularly given the revelation that the hospital had been billed insurance for CRPS-related care several months prior to her hospital stay. Instead, the doctors caring for Maya exchanged snide text messages calling Maya "Ketamine girl" and accusing her mother. Adding further insult to their irreparable injury, the hospital has also accused Beata of fraudulently acquiring injectable ketamine and giving it to her daughter at home without medical oversight, something she vehemently denied on an audio recording in the documentary.

What Maya Kowalski has said about her story

The double tragedy of living with severe chronic pain for most of her young life and losing her mother to suicide has forced Maya to grow up more than most her age. When her three long months of captivity finally come to an end, she felt grateful to finally return to normalcy but found herself faced with the fact that she would never see her mother again. Speaking to People, Maya said, "One day I was in the ICU, and my mom kissed me on the forehead and was like, 'I love you. I'll see you tomorrow.' I never saw her again."

In the aftermath of Beata's death and faced with a court order to avoid ketamine, Jack worried he would lose his daughter next. But eventually, with perseverance and a lot of therapy, she was able to walk without assistance once more. Despite everything she's been through, Maya says the fight isn't over. Although she has many good days, she tells People that the pain can still be excruciating. Nonetheless, Maya says, "I do my best to push through. I've already missed a lot, so I want to make the most of life now."

A lawsuit is currently pending against Johns Hopkins

While nothing can ever bring back their lost loved one, the Kowalskis believe a lawsuit is necessary to vindicate Beata while at the same time holding those responsible accountable to protect others in the future. As Jack Kowalski told the documentary crew, "We tried to cooperate. But nothing changes if you stay quiet. We have to hold Johns Hopkins responsible for what they've done."

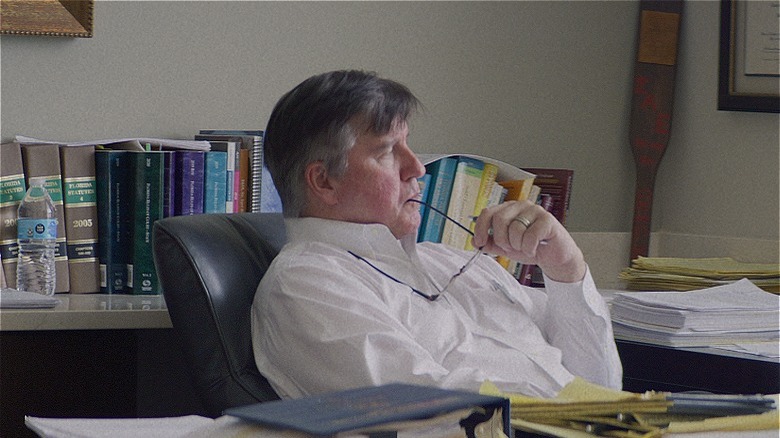

Although she wasn't able to help free her daughter from the hospital, all of Beata's documentation is now providing the framework for that litigation. Attorney Greg Anderson of AndersonGlenn LLP, the dynamo heading up the lawsuit, said in a statement to Daily Mail, "These events amount to an abduction, incarceration and abuse of a 10-year-old girl." The lawsuit — now set for a September 2023 trial date after a frustrating delay to jury selection in March 2023 — seeks a grand total of $55 million in compensation with $165 million in punitive damages for "battery and false imprisonment." Maya and Jack have given several depositions in the case thus far, and materials from these are used in the "Take Care of Maya" documentary.